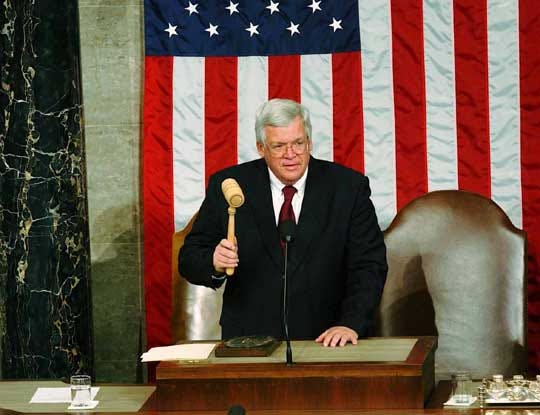

From Speaker to Smurf: Examining the Charges Against Dennis Hastert

The criminal charges against former Speaker of the House Dennis Hastert have raised some interesting questions, including questions about whether the case should have been brought at all. Hastert was arraigned last week in Chicago on an indictment charging him with one count of illegal structuring of bank transactions and one count of lying to the FBI.

Hastert served in Congress from 1981 to 2007 and was Speaker from 1999 to 2007. The indictment charges that over several years Hastert withdrew large amounts of cash in order to make payments to someone identified only as “Individual A.” Hastert allegedly had agreed to pay Individual A $3.5 million to compensate for, and keep concealed, prior misconduct by Hastert against Individual A. Although the indictment does not reveal the nature of the misconduct, several news outlets have reported that it involved Hastert sexually abusing a male student when Hastert was working as a high school teacher and wrestling coach in Yorkville, Illinois between 1965 and 1981.

From June 2010 through April 2012, Hastert allegedly made fifteen separate withdrawals of $50,000 in cash from several different banks and gave that cash to Individual A. Federal regulations require banks and other financial institutions to report any cash transactions in excess of $10,000, and in April 2012 the banks apparently questioned Hastert about the large cash withdrawals. After the banks started asking questions, Hastert allegedly began withdrawing cash in amounts just under $10,000, in order to avoid the bank reporting requirements.

The indictment charges that he made at least 106 such withdrawals between 2012 and 2014, again providing all the cash to Individual A. Hastert is alleged to have paid a total of $1.7 million in cash to Individual A over more than four years. In December 2014, the FBI interviewed Hastert concerning his unusual banking transactions. During that interview, Hastert told the FBI agents he made the withdrawals because he did not trust the banking system and that he was keeping the cash for his own use.

The Criminal Charges Against Dennis Hastert

Structuring: The structuring statute that Hastert is charged with violating, 31 U.S.C. § 5324, is part of the system of laws and regulations used to combat money laundering. In today’s economy, legal transactions involving large amounts of currency are relatively rare. But certain kinds of criminal activity, such as narcotics trafficking and organized crime, may generate enormous quantities of cash. Having all of this cash is no fun if you can’t spend it without arousing suspicion. Criminal operations therefore need to get their cash into the legal financial system and make it appear legitimate. That’s where the money laundering laws come in.

Money laundering takes aim at criminal activity from a different direction: it focuses not on the crimes that generate the money but on trying to freeze criminal proceeds out of the banking system and make it impossible for criminals to enjoy the fruits of their illegal activity. As part of this effort, banks are required to file a Currency Transaction Report (“CTR”) providing details about any cash transaction in excess of $10,000. This allows the government to track large flows of currency through the economy – not because dealing in cash is illegal, but because it is unusual and suggests potential criminal activity. The filing of a CTR does not mean a crime has been committed. It is simply a flag that something is going on that might merit a closer look.

Criminals would obviously prefer that CTRs not be filed, because they do not want to draw attention to themselves and their large, unexplained piles of cash. Thus the crime of structuring was born.

Suppose I am a drug dealer with $100,000 in cash from my illegal drug operations. I’d like to get that cash into a bank account so I could write checks, make wire transfers, and otherwise spend it without arousing suspicion. But if I take my duffel bag full of $100,000 in white-powder-encrusted tens and twenties and plop it down on the bank teller’s counter, people are (hopefully) going to start asking uncomfortable questions – not to mention filing CTRs.

One way I can avoid this problem is to get eleven of my associates to take $9,000 each and deposit the money in eleven different banks. No CTRs will be filed, and all of my money is now in the banking system ready for me to enjoy. This is the crime of structuring: designing your bank transactions specifically to avoid the filing of CTRs. It applies to both deposits and withdrawals.

Structuring is also known as “smurfing,” from the cartoon involving those cute little blue creatures, “The Smurfs.” I’m not sure how this nickname arose, but it may have to do with the image of many people scurrying around town to different banks to make deposits, just as the Smurfs used to scurry around their little Smurf village doing . . . whatever Smurfs do.

Hastert appears to have been engaged in textbook smurfing. He was withdrawing $50,000 in cash at a time, until the bank started asking questions. Then he deliberately reduced the amount of his withdrawals to just under $10,000, in order to avoid any more questions and to avoid the filing of CTRs.

False Statements: The other charge in the indictment is a violation of 18 U.S.C. § 1001, false statements. This is a widely-used white collar statute that prohibits knowingly providing material false information to the government. It differs from, and is much broader than, perjury, because statements do not need to be under oath. Lying to the FBI during an interview about something material to their investigation falls squarely within § 1001, and that is the basis of the charge against Hastert.

Issues Raised by the Hastert Indictment

One thing I find remarkable about this and many other white collar cases is that an accomplished and savvy person – in this case, someone who for years was third in line to be U.S. President -- ends up committing such a dumb crime. As a former Member of Congress, Hastert had to know that his cash transactions would raise flags. Even if he were determined not to leave a paper trail by simply writing checks, he could have used any number of more sophisticated and still secret ways to pay off Individual A. And when the FBI comes calling, why not decline to be interviewed, or simply call your lawyer? Is there some hidden, psychological desire to be caught involved here? If Dostoevsky were still around and had a blog, he’d have a field day.

An interesting question that remains unanswered is: how did the government learn about Individual A and his deal with Hastert? A bank report likely led the FBI to focus on Hastert’s financial transactions, but how did they progress from learning about the cash withdrawals to learning what Hastert was doing with the money? Did Individual A came forward independently (seems unlikely) to report the arrangement to the FBI? Did they tail Hastert and witness him making a payment to Individual A? Did they use phone records or some other investigative tool? We don’t yet know.

A related question concerns the treatment of Individual A by the prosecutors. Will he be charged with any crimes? Has he already pleaded guilty, with the proceeding under seal? Or did the government conclude that he committed no crime, or agree to grant him immunity? Some have argued that Individual A was plainly guilty of blackmail or extortion, and some (including Hastert himself) have suggested that Hastert was a victim, too. But we would need to know a lot more about the dealings between Hastert and Individual A, and how their arrangement came about, before making such a judgment. A mutual, consensual agreement, similar to an out-of-court settlement, would not amount to extortion.

Although there are lots of questions, it appears we won’t learn much more about Individual A any time soon, if ever. Prosecutors apparently have sought a protective order to cover any information they provide to the defense, to ensure that no one not involved in the case can see the material. If prosecutors have some kind of agreement with Individual A, it appears to include preserving his privacy for as long as possible.

Another interesting aspect of the case is the somewhat unusual application of the structuring laws. The money involved in Hastert’s cash transactions was not generated by criminal activity; this was “clean” money that legitimately belonged to Hastert. To that extent, the structuring charge falls outside of the heartland of activity at which the statute was primarily aimed.

Nevertheless, Hastert’s actions are a clear-cut case of smurfing. Unlike some other money laundering statutes, structuring does not require that the money involved be criminal proceeds. The purpose of the law is simply to enable the government to track large flows of cash through the banking system. Structuring thwarts that government interest, whether the money is clean or dirty. Even if the source of the cash is perfectly legal, large withdrawals may be a sign of other criminal activity.

The government had legitimate reasons to be questioning Hastert’s cash withdrawals. The transactions could have indicated that he was being extorted, perhaps even over something related to his time in Congress, or that he was involved in some other kind of criminal activity. That the government was asking these questions does not indicate any kind of overreach.

Should Hastert Have Been Prosecuted?

The issue then becomes whether, once the nature of the transactions was revealed, criminal charges should have been filed. In the wake of the indictment, some have questioned the decision to prosecute. They argue that Hastert appears to be a victim, that as a former powerful politician he has been unfairly singled out, and that the case is not a wise use of prosecutorial resources.

It's certainly true that not every instance of structuring results in a criminal prosecution. And if every witness who lied to the FBI during an interview were charged with false statements, federal prosecutors would have time to do little else. Deciding whether to file charges in such a case requires the sound exercise of prosecutorial discretion.

On this point I agree with another former AUSA, Jeffrey Toobin, who wrote in the New Yorker that he would not have hesitated to bring this case. A number of factors would enter into the charging decision. One would be the length of time and the number of violations – more than a hundred structured transactions over more than two years. This was not a one-off situation; Hastert knew what he was doing and did it repeatedly over a long period of time.

Another factor would be the nature of the misconduct that Hastert was concealing. Any sexual abuse that took place while he was a high school teacher could almost certainly not be prosecuted now due to the statute of limitations. But if Hastert committed more recent crimes in order to cover up that activity, prosecuting those crimes can serve the interests of justice.

Prosecution of cover-up crimes such as false statements or obstruction of justice does sometimes serve to ensure that defendants who committed crimes that are too old to be prosecuted do not entirely escape punishment. Particularly where the past criminal conduct was so egregious, that would weigh heavily in the decision about whether to prosecute. To me, at least, as a prosecutor this charging decision would feel very different if Hastert had been covering up past conduct that was legal but just embarrassing, such as an extra-marital affair.

Another factor in the charging equation would be Hastert’s outrageous lies to the FBI. This was not a hapless, unsophisticated defendant ensnared by some wily FBI agents. A former Member of Congress knew what he was doing, knew his legal options in terms of talking to the FBI, and knew the potential consequences of lying.

It’s also worth noting that the prosecutors, if they were truly vindictive and out of control, could have been a lot harder on Hastert. They likely could have charged him with more than 100 counts of structuring, one for each withdrawal. Instead they chose to charge the entire two-year structuring scheme as a single count, exposing him to a maximum of five years in prison for structuring rather than more than 500.

Personally I find it hard to feel sorry for Hastert. But to the extent the critics are correct and Hastert deserves some sympathy for the situation he was in, those considerations may be taken into account when it comes to sentencing, or in fashioning an appropriate plea agreement. That doesn't mean the charges themselves were not fully appropriate.

And finally, speaking of plea agreements, a quick guilty plea is by far the most likely outcome in this case. There’s not much in the way of a defense apparent from the indictment, and Hastert will almost certainly want to avoid a public trial where Individual A would testify about the past misconduct and their agreement. Hastert's best chance to avoid that information becoming public is to take a quick plea. But whether or not that happens, information like this has a way of coming to light. I expect before the case is over we will know a great deal more about Individual A and the circumstances that brought Hastert to this unhappy point.

Update 10/28/15: Hastert today pleaded guilty to one count of structuring his banking transactions.

Update 4/27/16: Hastert was sentenced today to fifteen months in prison, followed by two years of supervised release. He was also ordered to receive sex-offender treatments and pay $250,000 in fines.