What Andrew McCarthy Gets Wrong about the Mueller Investigation

National Review’s Andrew McCarthy has been a prominent critic of the Mueller investigation. Challenging everything from Mueller’s initial appointment to his investigative, charging, and plea bargaining tactics, McCarthy routinely portrays Mueller as a rogue prosecutor on an improper fishing expedition to bring down the president. In my view, many of McCarthy’s arguments don’t hold up. Although there are too many columns to discuss each individually, I will focus on some common themes that emerge from his writings and explain why I think he's wrong.

Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III

McCarthy's Attacks on Mueller’s Appointment

McCarthy frequently argues that Mueller’s appointment by Deputy Attorney General Rod Rosenstein was illegitimate because it failed to specify the crimes he is charged with investigating. He recently wrote:

To trigger the appointment of a special counsel, federal regulations require the Justice Department to identify the crimes that warrant investigation and prosecution — crimes that the Justice Department is too conflicted to investigate in the normal course; crimes that become the parameters of the special counsel’s jurisdiction.

Rosenstein, instead, put the cart before the horse: Mueller was invited to conduct a fishing expedition, a boundless quest to hunt for undiscovered crimes, rather than an investigation and prosecution of known crimes.

But the regulations don’t say that. The relevant section, 28 CFR 600.1, states that in order to appoint a special counsel DOJ must determine that a “criminal investigation” is warranted – not that specific crimes be identified and “known.” This may sound like semantics, but it is an important distinction. In a case involving a homicide or a bombing, for example, it’s usually clear from the outset that a crime has been committed - the crimes may be already "known." But that’s not true in many white collar investigations. These investigations often begin based on suspicious activity that may or may not turn out to be criminal. White collar cases often turn on what was going on in someone’s mind: Did they conspire to commit a crime? Did they act with corrupt intent? Proof of intent may require the painstaking assembly of evidence in the grand jury. By arguing that the order appointing a special counsel is required to specify “known crimes” to be prosecuted, it is McCarthy who puts the cart before the horse. Whether there is probable cause that crimes were committed is normally determined at the end of the investigation, not at the beginning. It's the identified need for an investigation that prompts the appointment of a special counsel, not the conclusion that there are already known crimes. Mueller’s appointment order specifies that it is based on the FBI investigation identified by then-director James Comey during his Congressional testimony on March 20, 2017. Comey testified the FBI was investigating Russian interference with the election and the possible involvement of members of the Trump campaign, and that the investigation included possible criminal violations. What that inquiry had already uncovered justified the appointment of a special counsel to continue the investigation. Even if Rosenstein had specifically named all the potential crimes uncovered to date, that would not be the full universe of crimes that might be discovered. And of course there are reasons you would not want to spell out all of those investigative details in a public order, while the matters and targets are still under investigation. Mueller’s investigation has already resulted in nineteen charged individuals and five guilty pleas – including guilty pleas from Trump’s former national security advisor and deputy campaign manager and the indictment of his former campaign manager. These facts alone belie any claim there was not sufficient indicia of criminal activity to justify a special counsel. In light of Mueller's results, it's hard to understand how McCarthy can continue to argue there was no basis for his appointment.

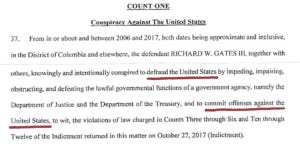

The Claim of a "New" Conspiracy Charge

In a recent column titled “Mueller’s Investigation Flouts Justice Department Standards,” McCarthy claims, as he has in the past, that Mueller has misused the federal conspiracy statute. He argues that Mueller charged Richard Gates and Paul Manafort with a “conspiracy against the United States,” and there “is no such offense in federal law.” As McCarthy notes, the federal conspiracy statute, 18 USC 371, prohibits two kinds of conspiracies: those to defraud the United States, and those to commit any offense against the United States. In the charging language in the 371 conspiracy counts brought by Mueller (paragraph 37 of the Gates superseding Information, for example) the indictment quotes this statutory language, and charges both kinds of conspiracies. Here’s the paragraph from the Gates Information:

It’s hard to understand exactly what McCarthy’s beef is here. His complaint seems to be that in the heading underneath the words Count One, prosecutors used a shorthand phrase – “Conspiracy against the United States” – to describe what appears below. But the charging paragraph itself properly mirrors the statutory language -- it's a valid and straightforward 371 charge. The phrase that McCarthy objects to is simply a caption; it's legally meaningless. “Conspiracy against the United States” seems like a reasonable title for a charge that includes both a conspiracy to defraud the United States and a conspiracy to commit offenses against the United States. But in any event, it’s wrong for McCarthy to rely on a caption, rather than the actual charging language, to claim that Mueller has made up a charge that does not exist in the criminal code. There's nothing new, exotic, or improper about Mueller's conspiracy charges.

Critique of the Conspiracy to Defraud Theory

McCarthy also claims that Mueller’s prosecutors have misapplied the “conspiracy to defraud the United States” portion of 18 USC 371. Mueller has charged a conspiracy to defraud the U.S. that consists of impairing, obstructing, or impeding the lawful functions of the U.S. government. He used this charge not only in the Manafort and Gates case but also in the indictment of thirteen Russian nationals, who were charged with conspiracy to interfere with the lawful functions of the federal government to regulate foreign campaign contributions and foreign lobbying activity. (I wrote last summer about the potential use of this theory in the Russia investigation, you can find that post here.) In a recent column, McCarthy rails against this theory. He claims the Supreme Court has never approved it and that prosecutors are relying on “extravagant precedents from federal circuit courts of appeal.” He also argues that in McNally v. United States, which struck down the honest services mail fraud theory, the Supreme Court held that to “defraud” means to obtain money or property by deceptive means. Based on McNally, he says:

The lesson is clear: The concept of fraud, including fraud on the government, is to be given its traditional, commonsense meaning of a deprivation of money or tangible property.

Because the “impair, obstruct or impede” theory of conspiracy to defraud does not involve a deprivation of money or property from the government, McCarthy argues, Mueller is simply making up crimes and distorting the law of fraud. This is plainly wrong. The Supreme Court has, in fact, specifically held that conspiracy to defraud the United States under section 371 includes conspiracies to impair, obstruct, or impede the lawful functions of the federal government. In the 1924 case of Hammerschmidt v. United States, the Court stated:

To conspire to defraud the United States means primarily to cheat the government out of property or money, but it also means to interfere with or obstruct one of its lawful governmental functions by deceit, craft or trickery, or at least by means that are dishonest. It is not necessary that the government shall be subjected to property or pecuniary loss by the fraud, but only that its legitimate official action and purpose shall be defeated by misrepresentation, chicane, or the overreaching of those charged with carrying out the governmental intention.

Hammerschmidt, a Supreme Court case, is cited (along with several other Supreme Court cases affirming the theory) in the exact same section of the U.S. Attorneys' Manual that McCarthy himself links to when he inexplicably claims that this legal theory has never been approved by the Supreme Court. What’s more, in the McNally case that McCarthy claims supports his argument, the Supreme Court expressly recognized and distinguished Hammerschmidt. The Court acknowledged that fraud for purposes of the federal conspiracy statute, which is aimed at protecting government functions, has a broader meaning than it does in the mail fraud statute at issue in McNally, which is aimed at protecting private property rights. (See 483 U.S. 358, fn. 8.) McNally's holding that fraud is limited to deprivations of money or property does not apply to the term "defraud" in section 371. The relevant Supreme Court precedent is the exact opposite of what McCarthy claims, and has been for nearly a century.

Former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort

The Attacks on Mueller’s Plea Bargains

In the same piece, titled “Mueller’s Investigation Flouts Justice Department Standards,” McCarthy also attacks Mueller for extending a favorable plea offer to Richard Gates in exchange for his cooperation against Paul Manafort. He claims that prosecutors are always required to make a defendant plead guilty to the most serious, readily provable charge against them. By allowing Gates to plead guilty to a 371 conspiracy – which carries a penalty of only five years – rather than a more serious charge of bank fraud, he claims, Mueller has violated that rule. He cites this plea bargain as evidence that Mueller is “shredding Department of Justice charging policy.” In this excellent post on the Lawfare blog, professor Orin Kerr does a little shredding of his own when it comes to McCarthy’s claims. As Professor Kerr points out, McCarthy ignores other DOJ policies that explicitly allow prosecutors to offer more lenient plea agreements when necessary to obtain a defendant’s cooperation. Prosecutors have a great deal of discretion when it comes to fashioning pleas and cooperation agreements. Indeed, in appropriate cases they may decline to charge people at all – even those who have committed very serious crimes – by granting them immunity in order to obtain their cooperation. Taken to its logical conclusion, McCarthy’s argument would make all of this impossible. McCarthy also professes outrage that Gates was allowed to plead to a section 371 conspiracy, with a maximum penalty of only five years, rather than a twenty-year money laundering conspiracy. He claims that when there is a conspiracy provision tailored to a specific statute that carries a greater penalty, prosecutors are required to use that conspiracy provision and are not supposed to charge 371. Although McCarthy repeatedly claims that prosecutors are required to adhere to the practice he describes, he doesn’t cite to any DOJ policy or rule spelling out that requirement. Perhaps he is relying on the same flawed argument debunked by Professor Kerr about the supposed requirement always to require a plea to the most serious charge. The plea agreement appears to be a good deal for Gates, but it doesn't violate any DOJ policy or practice. Any defense lawyer will tell you that seeking a conspiracy plea to place a five-year cap on the potential sentence is not an uncommon practice. It’s a way to limit your client’s exposure, and is one of the carrots prosecutors can offer in order to induce cooperation. Although McCarthy claims that "regular Department of Justice prosecutors" would never strike such a deal, that's not correct. To take just one example, in the prosecution of Enron executives Jeff Skilling and Ken Lay, the government’s star witness Andy Fastow was allowed to plead guilty to two counts of 371 conspiracy in exchange for his cooperation. That plea capped his maximum sentence at 10 years – even though had he gone to trial he would have faced more than twenty years in prison just like Skilling and Lay. This plea agreement came from the Enron task force, not a special counsel. That task force included some of DOJ’s top "regular" prosecutors – including Andrew Weissmann, Mueller’s top deputy. It’s unlikely such a plea deal would have been approved at the top levels of the Justice Department if it amounted to a “shredding” of DOJ policies.

Former National Security Advisor Michael Flynn

Criticism of the Michael Flynn Charge

McCarthy has also written several columns suggesting that former national security advisor Michael Flynn, who pleaded guilty to lying to the FBI, was unfairly set up. Flynn was interviewed by the FBI after administration officials stated publicly that Flynn had not discussed U.S. sanctions against Russia during conversations he had with Russian ambassador Kislyak during the transition. The FBI knew that was not true, because it had a tape recording of a call between Kislyak and Flynn where sanctions were discussed. As part of the FBI’s investigation into Russian contacts by the Trump campaign, they interviewed Flynn about his contacts with Kislyak. His lies during that interview, which took place less than a week after Trump’s inauguration, ultimately led to Flynn’s guilty plea. McCarthy has suggested that the FBI was out to get Flynn because he was an early Trump supporter and critic of the Obama administration. He writes there has “always been the cynical suspicion” (fueled in part by his own columns, no doubt) that there was no legitimate investigate purpose for the interview and that the FBI was seeking to trap Flynn into lying so it could charge him with a “process crime.” His strongest argument in support of this theory? He claims there was no need to interview Flynn about the phone call with the ambassador because the FBI already had a tape of the call. Therefore the interview must have been pretextual and part of a setup. But if you are conducting an investigation into contacts between Russia and the Trump campaign, there are many reasons to interview Flynn even if you have a tape of one phone call between him and Kislyak. Here are just a few things you would want to ask him: Who asked him to make the call? Who did he report to about the call? Have there been other calls that perhaps were not intercepted? Have there been face-to-face meetings between Flynn and Kislyak? Emails? Other communications? Was anything done as a result of the call? Were there any documents created to memorialize the call or any other contacts with Kislyak? Did he discuss the call with anyone else in the campaign? Does he know of others in the campaign who had contacts with Kislyak or other Russians? The list goes on and on. To fail to interview Flynn would have been investigative malpractice. There’s no basis to believe he was set up. Suggesting otherwise simply feeds into the “deep state” conspiracy theories about how the FBI was out to get Trump while ignoring supposedly more serious infractions by Hillary Clinton (another common McCarthy complaint).

Claimed Omniscience about the Investigation

Throughout his columns, McCarthy frequently claims to know what is going on in the FBI and Mueller investigation. For example, he knows there was no legitimate basis to appoint a special counsel. He knows that no evidence of collusion has been uncovered. He knows there was no legitimate reason to interview Flynn. He knows that Flynn’s guilty plea to false statements means there is no evidence of a larger conspiracy. And so on. The truth is that these are all speculations, not facts. All of us, including McCarthy, probably know less than ten percent of what Mueller and the FBI know about the Russia investigation. But McCarthy routinely asserts as truths things that are merely his personal beliefs. He’s entitled to his theories, of course, but too often he fails to acknowledge that that’s what they are. McCarthy is a prominent voice on a well-known platform. It’s unfortunate that so much of what he puts out about the Mueller investigation is incorrect. Although many readers will believe him when writes that Mueller is flouting DOJ policies and making up illegitimate charges, it's really -- if you'll forgive me -- fake news.

Like this post? Click here to join the Sidebars mailing list