The Capitol Riot, Infowars, and the Definition of Journalism

Earlier this summer, Attorney General Merrick Garland announced revisions to the Department of Justice internal rules on obtaining records from journalists. With limited exceptions, the policy provides that DOJ will not subpoena information from members of the “news media” who were engaged in “newsgathering activities.” Now a case arising from the January 6 Capitol riot has highlighted a question posed by this policy: who qualifies as a member of the news media entitled to its protections? More specifically: is the conspiracy-touting, right-wing website Infowars engaged in journalism? The answer to this question has implications far beyond cases involving the insurrection at the Capitol.

The Owen Shroyer Case

Jonathon Owen Shroyer is the host of a daily program that streams on Infowars, “The War Room with Owen Shroyer.” Infowars is a “news service” website led by Alex Jones. Jones and Infowars are noted for promoting various conspiracy theories, including that the 2012 shooting of twenty children and six adults at Sandy Hook elementary school was faked and that a Washington, D.C. pizza parlor housed a child sex trafficking ring associated with Hillary Clinton – a conspiracy hoax that became known as “Pizzagate.” Jones, Shroyer, and Infowars have been banned from most social media sites for spreading disinformation.

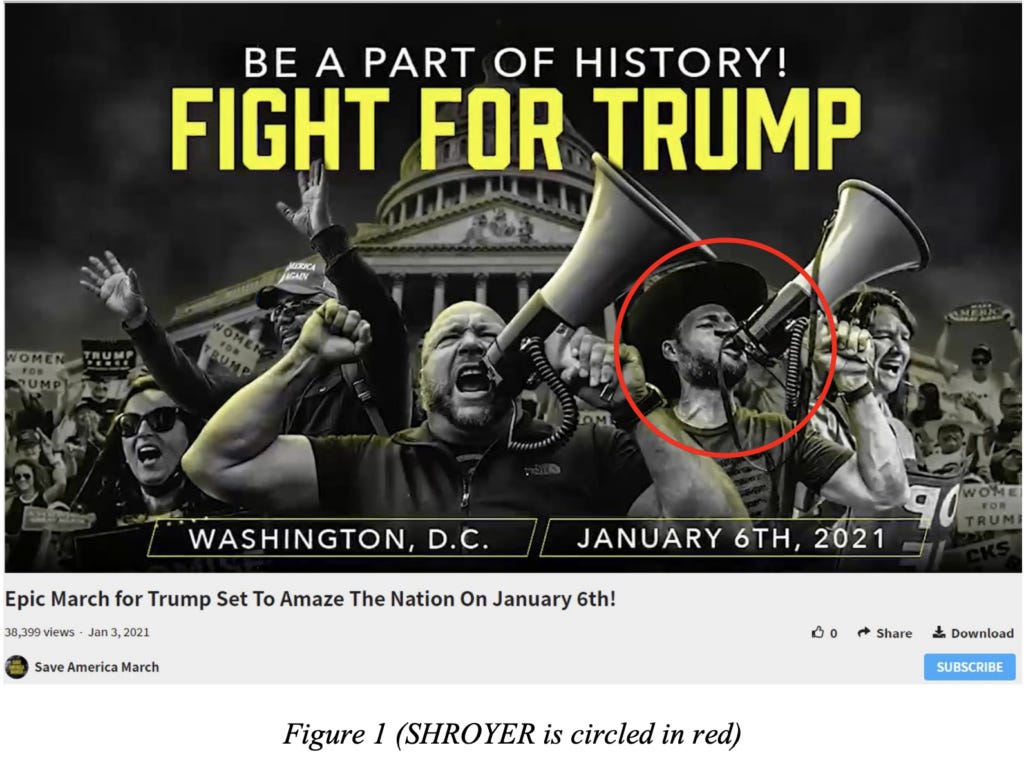

Infowars was a favorite of former president Trump, who routinely praised Jones and echoed the site’s outrageous claims. Infowars also played a significant role in helping perpetuate the “big lie” that the 2020 presidential election was stolen. After Trump lost re-election, Shroyer led a nine-city tour of “Stop the Steal” rallies. He was also featured in materials published by Infowars promoting the January 6, 2021 rally in Washington and urging people to attend and “fight for Trump.”

On January 5, Shroyer spoke at a rally at Freedom Plaza in D.C. where he said, “Americans are ready to fight! . . . We are the new revolution!” Video footage allegedly shows him taking part in marching to the Capitol on January 6, exhorting the mob to stop the election from being “stolen,” and leading the crowd in a chant of “1776!” At one point during the rally, he called live into an Infowars broadcast and reported, “They’ve taken the Capitol grounds, they’ve surrounded the building itself, they’re on the actual building structure. . . . We literally own these streets right now.”

Last week, Shroyer was arrested for his role in the Capitol riot and appeared in court in Washington, D.C. Prosecutors have charged him with entering a restricted area of the Capitol and with unlawfully attempting to impede the work of Congress. Both offenses are misdemeanors. It appears he will maintain that he was covering the events in Washington as a journalist for Infowars.

The Judge’s Inquiry

On August 19, U.S. Magistrate Judge Zia Faruqui held a telephone conference with prosecutors regarding the arrest warrant for Shroyer. Faruqui asked prosecutors whether they considered Shroyer a member of the news media and whether they had complied with the new DOJ media regulations when investigating him. Prosecutors said they had followed the guidelines, but declined to provide specifics. This caused Faruqui to issue an opinion a few days later, expressing his displeasure. He claimed that prosecutors in other cases have provided more details about their compliance with the regulations, and it troubled him they did not do so here: “The Department of Justice appears to believe that it is the sole enforcer of its regulations. That leaves the court to wonder who watches the watchmen.”

Faruqui’s opinion is a little odd, in that it doesn’t order the prosecutors to do anything. He ultimately signed the arrest warrant, concluding that even if Shroyer was a journalist there was ample evidence that he committed a crime. It appears Faruqui just wanted to make a clear record of his request and of his concerns about whether DOJ was in fact following its own media guidelines.

In a letter to the court, John Crabb, Jr., Chief of the Criminal Division at the U.S. Attorney’s Office, responded with the polite legal equivalent of, “Buzz off.” Crabb wrote that enforcing internal regulations like the media guidelines is committed to DOJ’s sole discretion. It is not the court’s role, he argued, to police DOJ’s application of internal policies that have nothing to do with the finding of probable cause. He also argued that such inquiries by the court might impede “frank and thoughtful deliberations within the Department” about how to apply the regulations.

Crabb is clearly right here, and Faruqui was out of line. The DOJ “Justice Manual” contains many policies about how to interpret and enforce certain areas of the law. Department attorneys may be subject to internal discipline for failing to follow those policies. But it is well-established that those policies do not create rights that may be enforced by outside parties. These are voluntary internal operating rules, not laws passed by Congress.

If Shroyer believes he has some kind of First Amendment defense based on his alleged status as a journalist, he can file a motion and the judge can rule on it. But under the separation of powers, it’s not Faruqui’s role to probe DOJ’s application of its own voluntary policies that have nothing to do with the legal merits of the case. At some level Faruqui himself seems to recognize this, since he issued his opinion but did not require DOJ to do anything in response.

DOJ’s Media Guidelines

As noted above, Faruqui’s inquiry was based on DOJ’s recently-modified guidelines about subpoenas to members of the media. Those guidelines have been around in various forms for decades. They represent the Department’s effort to balance the needs of law enforcement with the important First Amendment interests of the news media in gathering information without fear of government interference or punishment.

Journalists have long argued that they should have a legal privilege to refuse government demands for information about their reporting and sources. They claim such a privilege is necessary to protect the vital role of the free press in rooting out government misconduct. They argue that, absent such a privilege, government leakers and other sources of information who may fear reprisals if discovered will refuse to speak to reporters. Just as communications to lawyers and doctors are shielded from disclosure by the legal system, they argue, communications to journalists should be protected in order to ensure the free flow of information to the public.

[Side note: I think the arguments for the reporter’s privilege are wrong and that the privilege is a bad idea. I’ve written a lot on that topic – including in the very first post on this blog. Those arguments are beyond my scope here, but if you are interested in a deeper dive you can check out my blog posts here, here, and here, and law review articles here and here.]

In the landmark 1972 case of Branzburg v. Hayes, the Supreme Court held that the First Amendment does not create a privilege that allows journalists to refuse to testify, at least in federal criminal proceedings. In the aftermath of Branzburg, DOJ adopted its media guidelines, recognizing that even if the Constitution did not require it, DOJ should recognize the First Amendment interests at stake and exercise its discretion not to pursue information from journalists in most cases.

Battles Over the Reporter’s Privilege

There have been a few high-profile fights between DOJ and journalists who resisted complying with court orders to reveal information about their sources, although overall such cases are quite rare. Perhaps the most notable example involved New York Times reporter Judith Miller, who was jailed for nearly three months in 2005 when she refused to reveal her source to a grand jury investigating the leak of a CIA agent’s identity. (Vice president Dick Cheney’s chief of staff, Scooter Libby, was ultimately convicted of perjury and obstruction of justice in that investigation. Libby was pardoned by president Trump in 2018.)

Another dispute involved yet another New York Times reporter, James Risen, who refused to reveal his source for a story that revealed classified information about a covert U.S. government operation in Iran. Risen took his fight all the way to the U.S. Supreme Court, and the courts ruled he had no privilege and could be compelled to testify. Risen made it clear that he, like Miller, would go to jail rather than comply. The government ultimately backed down, chose not to call him as a witness, and managed to convict the source, Jeffrey Sterling, without Risen’s testimony.

During the Obama administration, the Justice Department under Attorney General Eric Holder was strongly criticized by media organizations for its pursuit of those who leaked classified information to the press. Obama’s DOJ was accused of engaging in a “war on the press” -- a ridiculous charge, as I explained here. Nevertheless, responding to that criticism, Holder held meetings with media representatives and updated the DOJ guidelines to make it even more difficult for prosecutors to subpoena information from journalists. In general, such information could be sought only when it was vitally important to the case, when alternative avenues to obtain the information had been exhausted, and when the request was approved by high level DOJ officials.

Early in the Biden administration, DOJ disclosed that Trump’s Justice Department had secretly sought email and phone records of several reporters at the Washington Post, New York Times, and CNN, in connection with investigations of leaks of classified material. When asked about the disclosures, Biden said that seeking such records from journalists was “simply wrong” and that he would not allow it in his administration.

As a result, last July 19, as noted above, Garland issued a memo saying the media guidelines would be amended again and would now contain a flat prohibition on the use of compulsory process to seek information from members of the news media who were engaged in newsgathering activities. (There are still some limited exceptions, such as when the journalist himself is under investigation for committing a crime, is an agent of a foreign power, or when disclosure is necessary to prevent imminent risk of death or serious bodily harm.) These are the updated guidelines about which Judge Faruqui was inquiring in the Shroyer case.

Is Shroyer a Journalist?

The DOJ media guidelines have been around for decades but have never defined who qualifies as a journalist under those guidelines. The governing regulations associated with those guidelines provide that whether someone is a member of the “news media” engaged in “newsgathering activities” must be determined on a case-by-case basis – but provide no guidance on how to make that determination. So is Infowars engaged in journalism, and is Shroyer a journalist?

Unlike professions such as law or medicine, which also enjoy certain legal privileges, there are no particular educational or licensing requirements to help define who is a journalist. In one sense, journalism is more of a process than a profession. Merriam-Webster defines journalism as “the collection and editing of news for presentation to the public.” This could include anyone from a reporter for a national newspaper to a pajama-clad blogger working from home. The First Amendment's protections apply equally to all such speakers and do not depend on the popularity of the views being expressed.

Fifty years ago, when media consisted primarily of newspapers, magazines, and the three major television networks, the Supreme Court observed that attempting to define who is a journalist for purposes of a legal privilege would be a “questionable procedure” that would “present practical and conceptual difficulties of a high order.” The rise of the Internet and the explosive growth of the media universe in the decades since have made that task exponentially more difficult. Now anyone with a cell phone can potentially disseminate information to millions of people and claim to be engaged in citizen journalism.

For years, efforts to enact a federal reporter’s privilege statute in Congress have foundered, at least in part, over the problem of defining who is a “journalist” entitled to invoke the privilege. Any such definition necessarily puts the government in a position of deciding which First Amendment speakers are “real” journalists deserving of special legal protections – a dubious Constitutional exercise. Even some in the media have opposed the idea, arguing that it amounts to allowing the government to license journalists.

One proposed solution is to limit the definition of journalists to those who make a substantial portion of their livelihood by gathering and disseminating news to the public. But that has problems as well. Such a definition tends to favor large, established media organizations and their staff over small, independent bloggers and other upstarts who may work for little or no money but often break major stories. And if the purpose of a privilege is to increase the flow of information to the public, it doesn’t make much sense to shield the communications of a reporter for a small local paper with a few hundred readers but not those of an independent blogger with a readership in the millions.

Shroyer allegedly participated in the riot, but at the same time was broadcasting information concerning what was happening to Infowars’ substantial audience. That portion of his activities, at least, would seem to qualify as journalism. But if Shroyer broadcasting live scenes from the Capitol qualifies, how about an individual blogger who attended and posted scenes on Facebook live or on her own blog? That person, too, is providing information to the public – the essence of journalism. Should the blogger also be shielded from investigation by the DOJ policy? Should subpoenaing the Facebook posts to further the investigation of the riot now be off-limits?

Lawyers love “slippery slope” arguments, and sometimes the dilemmas they pose are overstated. But defining who qualifies as a journalist and who doesn’t is a real problem with significant constitutional implications – at least if you are talking about granting special legal privileges to journalists that other First Amendment speakers do not enjoy.

What’s At Stake

Journalists can’t commit crimes in the course of reporting and claim they are immune. A reporter cannot, for example, break into someone’s office to steal documents and then defend herself by claiming she were working on a story. Whether or not Shroyer is a journalist is not going to determine whether he can be prosecuted. Judge Faruqui recognized that when he signed the arrest warrant even while questioning whether Shroyer was a member of the media. But Shroyer’s case does highlight the minefields for law enforcement in this area.

In the Internet age, the number of people who can credibly call themselves journalists, or say they are engaged in gathering news for delivery to the public, has grown dramatically. A policy that declares the records of any such person to be off limits has the potential to put a great deal of information outside the reach of law enforcement. That could severely hamper efforts to investigate not only major crimes like the Capitol riot but more everyday incidents as well.

It’s one thing if this is just an internal DOJ policy. That leaves the Justice Department free to investigate cases like Shroyer’s when it determines the policy does not apply – even if the occasional judge Faruqui improperly tries to look over prosecutors' shoulders. But when announcing the updated guidelines, Garland also said DOJ would support Congressional efforts to enact a federal reporter’s privilege statute. If that happens, then a whole new generation of Internet “journalists” like Shroyer will routinely will invoke that legal privilege to resist requests for information, fight subpoenas, and seek to thwart prosecutions.

DOJ should be careful what it wishes for. By endorsing federal legislation that prohibits seeking information from all those engaged in “newsgathering,” DOJ would hand a weapon to defendants like Shroyer who seek to shield their criminal activities. Congress should think twice before putting the force of federal law behind such a weapon.

Like this post? Click here to join the Sidebars mailing list