Conspiracy charges play a key role in the criminal cases against Donald Trump, particularly in the D.C. and Georgia prosecutions. There’s already a lot of misinformation and confusion – some in good faith, some not – floating around about the crime of conspiracy. As these prosecutions get underway, it seems like a good time for a brief primer on conspiracy law.

The Conspiracy Charges in the Trump Cases

D.C. Federal Case – The four-count indictment in D.C. against Trump alone includes three counts of conspiracy:

conspiracy to defraud the United States

conspiracy to obstruct justice, and

conspiracy to deprive another of their civil rights.

Georgia State Case – The Georgia indictment charges Trump with taking part in seven different conspiracies with some or all of his 18 co-defendants:

conspiracy to violate RICO

conspiracy to impersonate a public officer

conspiracy to commit forgery (2 counts)

conspiracy to make false statements and writings (2 counts), and

conspiracy to file false documents.

Florida Federal Case – Of the forty-two counts in the Florida Mar-a-Lago documents case, one count charges Trump and his two co-defendants with conspiracy to obstruct justice.

New York State Case – The New York state hush-money payments case is the only one that does not include any conspiracy charges. It charges Trump alone with 34 counts of filing false business records.

A Partnership in Crime

The simplest way to think of a conspiracy is as a partnership in crime. It’s an agreement to do something illegal.

Different conspiracy statutes differ slightly, but in general to prove a conspiracy charge the government must prove:

Two or more people formed an agreement to do something the law forbids

The defendant voluntarily joined the agreement knowing about its criminal objective and with the intent to help it succeed

Some conspiracy statutes also require the government to prove at least one “overt act” was committed in furtherance of the conspiracy. More about that below.

A conspiracy to commit a crime is a separate offense from committing the crime that is the conspiracy’s goal. As the Supreme Court has said, the conspiracy is considered a “distinct evil” that may be separately prosecuted and punished.

Even if the conspirators never successfully complete crime X, they can still be prosecuted for conspiring to try. It doesn’t matter why the conspiracy failed. The conspirators may have simply been unsuccessful, may have abandoned their plan, may have been thwarted by law enforcement, or may have found that their plan was impossible. Regardless of the reason, the conspiracy itself may still be punished.

Why Punish Conspiracy?

Criminal law punishes conspiracies, even if they don’t succeed, because of the dangers of group criminal activity. People who pool their physical, mental, and economic resources by agreeing to break the law can engage in more complex crimes and do more harm that individual actors. There’s a reason the hit movie “Ocean’s Eleven” is not called “Ocean’s Solo” – it’s hard to rob the Bellagio casino all by yourself.

Those who act in a group are also less likely to back down or rethink their plans, as group dynamics such as peer pressure and mutual reinforcement come into play. People will do things as part of a group they might be much more hesitant to do on their own. We need look no further than the Capitol riot on January 6, 2021 for one extreme example.

Simply put, people criming together are more dangerous and can cause greater harm. Conspiracy law punishes and seeks to deter this group criminality.

Why Prosecutors Love Conspiracy Charges

A famous quote from an old court case calls conspiracy “the darling of the modern prosecutor’s nursery.” It is a go-to charge for prosecutors in any large and complex case involving multiple actors.

A conspiracy charge provides a great framework for a speaking criminal indictment. By its nature it allows prosecutors to lay out the details of a criminal scheme, all the players and their roles, and every step they took to execute it. It’s very common for prosecutors in a large case to lead with conspiracy as Count One and use that charge to tell the entire story of the case – usually consuming the bulk of the indictment. Both the D.C. and Georgia indictments use this structure.

Conspiracy allows prosecutors to bring all defendants who took part in a scheme together for a single trial in a single courtroom – from the ringleaders to the bit players. Venue for a conspiracy charge for all co-conspirators is proper in any district where any one of them performed an act in furtherance of the conspiracy. That’s why, for example, Trump and other D.C. officials can be charged with conspiracy in Georgia even if they never set foot in the state.

Conspiracy charges can provide evidentiary advantages in some cases. For example, out of court statements that might otherwise be hearsay are admissible in a conspiracy case if they were made by a co-conspirator in furtherance of the conspiracy.

Conspiracy law also provides a way to punish those who may participate in planning criminal activity but then are not part of the “boots on the ground” group that carries it out. For example, in the Georgia case Trump is charged with conspiring to commit forgery and conspiring to file false documents for taking part in the scheme to have fake electors send their documents to Washington. But because he did not sign and file the documents himself, he is not included with the other defendants who are also charged with actual forgery or false filings.

Proving the Agreement

The agreement is the heart of any conspiracy charge. Prosecutors must prove that the defendant entered into a criminal agreement. Of course, co-conspirators do not usually memorialize their criminal agreements in signed contracts. Proving the agreement requires proving what was going on in someone’s head, a common challenge in white collar cases.

The best way to prove the agreement is to have one or more of the participants in the conspiracy testify about it. This is another reason prosecutors love a conspiracy charge. In a case like Georgia, with 19 indicted co-conspirators, the charge provides a great incentive for some of the lower-level players to “flip,” cut a deal, and testify for the government.

But even in the absence of a cooperator, it’s often relatively easy for prosecutors to prove an agreement through circumstantial evidence.

For example, suppose you and I drive to a bank together, pull stockings over our heads, enter together, rob the tellers at gunpoint, and then drive away together. What are the odds that this was all just a really weird coincidence? Obviously we had an agreement to commit the robbery. When we are prosecuted for conspiracy to commit armed robbery, even if neither of us testifies about our agreement, a jury will be entitled to find that agreement beyond a reasonable doubt based on the circumstantial evidence of our actions.

Indicted and Unindicted Co-Conspirators

Every conspiracy requires two or more human actors who form the agreement. But that doesn’t mean all conspirators have to be charged at the same time or in the same indictment.

The Trump cases provide examples of several variations on this theme. (And let’s just pause here for a moment to reflect on how remarkable it is that any single defendant, much less a former president, could be indicted in enough different cases to provide “several variations.”)

In the D.C. case, Trump is the only defendant. The indictment lists six co-conspirators who participated in the scheme but does not charge them. These “unindicted co-conspirators” are identified only by a pseudonym, as is the Justice Department practice: Co-Conspirator 1, Co-Conspirator 2, etc. They may be charged separately in a future case or they may be added to the indictment later via a superseding indictment (as happened in the Florida case). They may plead guilty without being indicted and potentially cooperate with prosecutors at Trump’s trial. They may have been granted immunity and compelled to testify. Or they may never be charged at all -- although that seems unlikely.

In the Florida Mar-a-Lago documents case, Trump was initially charged with co-defendant Walt Nauta. One of the counts charged the two of them with conspiracy to obstruct justice. A superseding indictment added the third defendant, Carlos Oliveira, and that charge of conspiracy to obstruct was expanded to include all three of them.

In the Georgia case, Count One charges all nineteen defendants with taking part in a RICO conspiracy. The charge also refers to the participation of thirty other unindicted co-conspirators (which has led to a great parlor game among commentators trying to sleuth out who those unindicted co-conspirators might be, based on clues in the indictment). Later counts charge Trump with conspiring with one or more of the other defendants to commit various crimes.

Overt Acts

At common law a conspiracy conviction required proof that at least one co-conspirator committed at least one “overt act” in furtherance of the conspiracy. Some modern conspiracy statutes have done away with this requirement, but the primary federal conspiracy statute used in the D.C. federal case, 18 U.S.C. § 371, requires an overt act, as does the Georgia RICO statute.

The overt act requirement is intended to prevent the government from prosecuting mere thought crimes. It is evidence that the co-conspirators have begun to put their plan into action. I may sit around at a bar with a couple of friends and come up with a plan to set up a phony investment website and defraud investors. But if in the morning when we sober up we never take any steps to carry out our agreement, a theoretical charge of conspiracy to commit wire fraud would fail for lack of any overt act.

Overt acts must take place during the life of the conspiracy and must further the conspiracy. Prosecutors only need to prove one overt act committed by one member of the conspiracy, although they frequently allege dozens or more (the Georgia indictment lists 161). Spelling out the overt acts in chronological order is a very effective way for prosecutors to tell the story of their case, step by step.

There is no requirement that each member of the conspiracy commit an overt act, or even that all other members knew about the details of overt acts committed by their co-conspirator. The partners in crime are responsible for each other’s actions.

Practically speaking, the overt act requirement today doesn’t add much to a conspiracy charge (which is why some more recent conspiracy statutes omit the requirement altogether). In any case that any prosecutor would ever seriously think about charging, there usually will be an abundance of overt acts to choose from. No modern conspiracy prosecution fails for lack of an overt act. The main challenge for prosecutors is usually trying to decide which ones to include as part of the indictment.

Overt Acts Need Not Be Illegal . . .

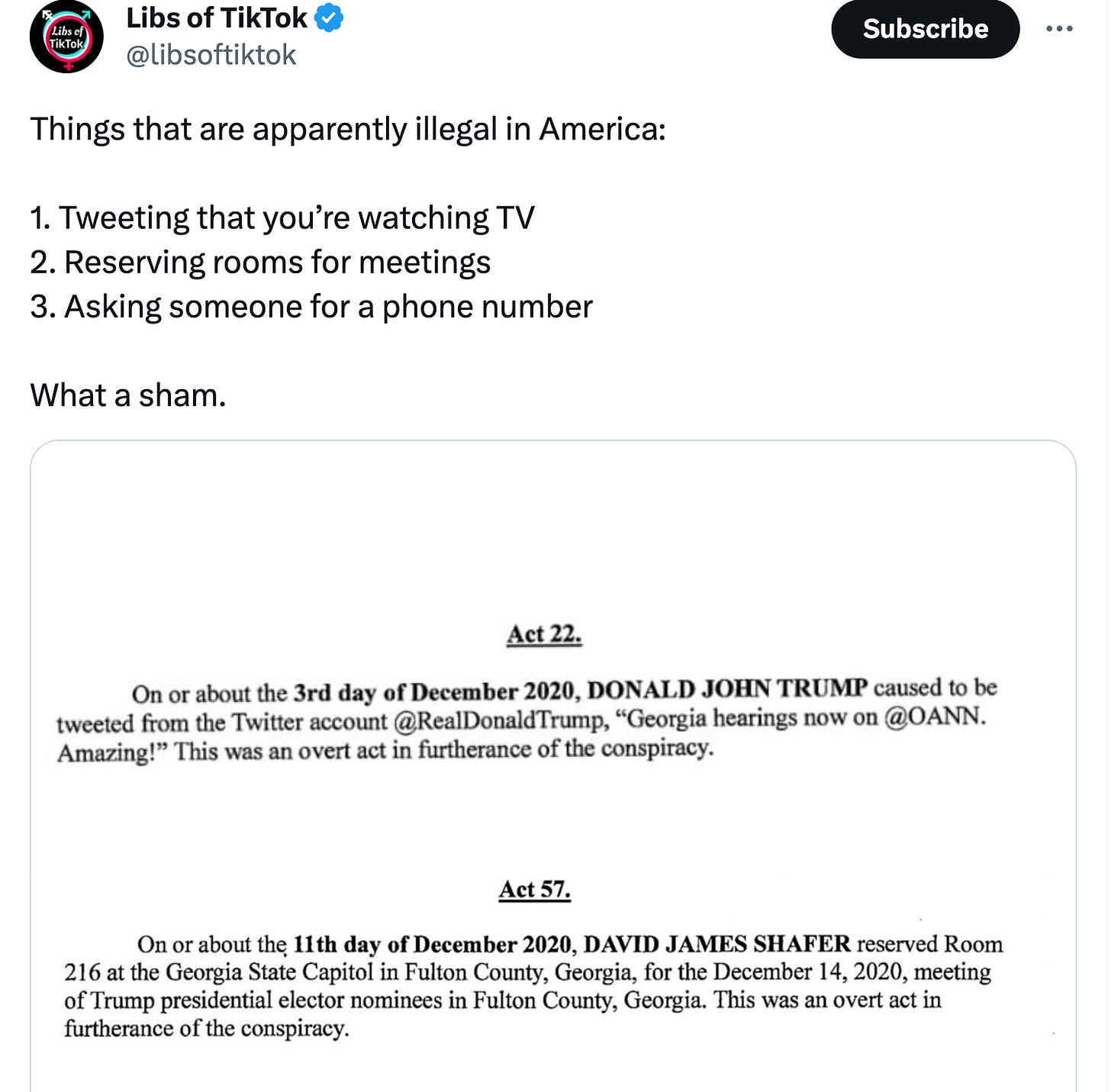

A common conservative response to the Georgia indictment was to ridicule it by picking out individual overt acts and claiming Georgia is now saying that act is a crime. For example:

This is straight-up misinformation. Overt acts do not need to be illegal. They are not the crime, they are simply steps taken to try to carry out the conspiracy.

My favorite example to use in class to illustrate this comes from the indictment of Martha Stewart and her stockbroker Peter Bacanovic. In the lead conspiracy charge, one of the overt acts alleged was:

On or about January 16, 2002, in New York, Martha Stewart and Peter Bacanovic met for breakfast.

The government’s evidence was that during the meeting the defendants came up with the phony cover story they would tell the FBI and SEC about why Stewart sold her stock, to conceal that she had received an improper tip from Bacanovic. The breakfast meeting, although perfectly legal, was an overt act in furtherance of their conspiracy to obstruct the investigation.

If this indictment came down today, you’d see Stewart’s supporters posting online: “GOVERNMENT SAYS EATING EGGS BENEDICT IS A CRIME!”

Or maybe, ‘THEY’RE COMING FOR YOUR BACON!”

Don’t be misled by all this bad-faith chatter. There’s nothing wrong with overt acts that would otherwise be legal and innocuous.

. . . But they CAN be Illegal

Overt acts do not need to be crimes themselves -- but they can be. For example, suppose I and others enter into a conspiracy to rob a bank. We need guns for the robbery, so I break into a gun dealer and steal several weapons. That’s a burglary for which I can be prosecuted. But that burglary could also be listed as an overt act in furtherance of the robbery conspiracy – a step that I took in furtherance of that conspiracy to help carry it out.

Unfortunately the Georgia indictment, by mixing up legal and illegal overt acts, has contributed to the confusion surrounding overt acts. The RICO conspiracy lists 161 different acts in furtherance of the conspiracy. Some of them are identified as just overt acts that are not otherwise illegal. Others are both overt acts and separate crimes, for which some of the defendants are charged later in the indictment.

The indictment would have been clearer if these different types of acts were broken out into different categories, to distinguish the mere overt acts from those acts that were independently criminal. Lumping them all together has made it easier for critics to attack the indictment by blurring the differences.

Conspiracy to Defraud the United States

Most of the conspiracy charges Trump is facing allege a conspiracy to commit a particular crime: conspiracy to obstruct justice, conspiracy to file false documents, etc. That is the most common type of conspiracy charge. But the lead conspiracy count in the D.C. indictment is a different kind of animal.

The primary federal conspiracy statute is 18 U.S.C. § 371. There are two different ways to violate the statute. The first is a conspiracy to commit an offense against the United States, which simply means a conspiracy to commit any federal crime. But the second prong of 371 prohibits any conspiracy to “defraud the United States.”

Longtime Sidebars readers will recall several posts over the years about the legal definition of “defraud.” In a string of cases going back several decades, the Supreme Court has consistently held that to defraud someone means to deprive them of money or property. The Court has consistently rejected efforts by prosecutors to expand the reach of the mail and wire fraud statutes to include deprivations of other intangible or non-economic interests. Recent examples include the Court’s unanimous rejection of federal fraud charges in the New Jersey “Bridgegate” case and two decisions just last spring that reaffirmed this narrower definition of fraud.

But a section 371 conspiracy to defraud the government has a different and broader meaning. For nearly 100 years the Court has held that schemes to defraud the government under 371 include schemes to interfere with or obstruct lawful government operations through deceptive or dishonest methods, even if no loss of money or property was involved.

The 1987 case of McNally v. United States began the string of Supreme Court cases limiting mail and wire fraud to deprivations of money or property. It rejected the government’s theory that fraud included deprivations of the intangible right of honest services. In dissent, Justice Stevens argued that the majority’s narrow definition of fraud in the mail and wire fraud statutes made no sense because the exact same word in the conspiracy statute, 371, had been interpreted more broadly to include non-property interests.

In a footnote the majority responded, in effect, “371 is different.” Because the statute is aimed at protecting the functions of the federal government and not just private property interests, a broader definition is appropriate. The majority quoted with approval a decision from the First Circuit Court of Appeals:

“[a] statute which . . . has for its object the protection of the individual property rights of the members of the civic body is one thing; a statute which has for its object the protection and welfare of the government alone, which exists for the purpose of administering itself in the interests of the public, [is] quite another.”

Jack Smith’s lead charge in the D.C. case is this kind of conspiracy to defraud the United States. Count One charges that Trump conspired with others to obstruct and defeat the lawful government function of certifying the electoral vote count on January 6, 2021, through a variety of deceptive and dishonest means.

You might see critics suggesting this conspiracy to defraud charge is flawed because it does not charge a deprivation of money or property. But under section 371, the charge is solid and supported by nearly 100 years of Supreme Court precedent.

If you found this review useful, I hope you’ll share it with your own network. Thanks!

Hi Randall,

Thanks for starting this very useful Substack. Like you, I was a longtime AUSA (EDVA). I have a few questions that perhaps you could address. I think they would be of general interest to your readership.

First, I was wondering whether you had a response to Harvard Prof. Jack Goldsmith's thoughtful piece in the NYT, here: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/08/08/opinion/trump-indictment-cost-danger.html?fbclid=IwAR0Wqe6E3pW7iHtOPY0RoLGLAFCaWUz24e8Zg7qqRqLqZ00hI5YXqVWNqrI Prof. Goldsmith can't stand Trump and what Trump represents, but still, I thought, made some fair points.

Second, I was wondering if at some point you could do something like a "Frequently Asked Questions" piece on the Trump prosecutions. One question would be, for example, whether it makes a difference if Trump truly believed he won the election. I know you've taken that on before, but I wonder whether, assuming he had such a belief, that would affect the government's obligation to prove that he acted "corruptly" in seeking to persuade/coerce election officials.

Another question might be whether the actual or perceived difference in DOJ's determination to go after Trump versus, for example, Hillary or Hunter could or should affect public perceptions of this prosecution.

A fourth might be what to make of the fact that the Georgia indictment charges so many of Trump's attorneys. When I was an AUSA. I always thought long and hard before going after a defense attorney no matter how sleazy and dishonest I thought he was (although I did go after one fellow who was laundering money for his supposed client).

And one more might be where, specifically, the law should draw the line between questioning the results of an election (which is legal), and seeking to change those results or simply bully the vote counters (which obviously is illegal). I don't know that I have a precise answer to that question, and it would make a difference to what is sure to be Trump's First Amendment defense. SCOTUS of late has been quite protective of First Amendment claims, as (in my view) it should be.

To say the least, this will be one of the most closely watched criminal cases in American history, and I think it important that the public perceive that Trump was treated fairly. Full public acceptance of his forthcoming convictions probably cannot be achieved, given how impervious some of his supporters are, but that makes the perception of open-minded people all the more important.

Again, thanks for your work on this Substack.