What do one of baseball’s greatest players, a former senior White House official, a domestic diva and Fortune 500 CEO, and a former Speaker of the House all have in common?

This is not the beginning of some bad joke about how they all walk into a bar. Barry Bonds, Scooter Libby, Martha Stewart, and Dennis Hastert all were investigated for possible criminal misconduct and ended up being charged not with that misconduct but with other crimes they committed to try to conceal their actions or thwart the investigation.

Barry Bonds was implicated in baseball’s steroids scandal. He ended up being indicted not for using illegal steroids but for perjury and obstruction of justice after allegedly lying in the grand jury about his steroid use. (He was found guilty of one count of obstruction, but that conviction was recently overturned on appeal.)

I. Lewis “Scooter” Libby, who was Chief of Staff to former Vice President Dick Cheney, was implicated in the potentially illegal leak of the identity of a covert CIA agent, Valerie Plame. He was ultimately not charged with the leak but was convicted of perjury, obstruction of justice, and false statements for lying to the grand jury and the FBI about his actions.

Martha Stewart was suspected in 2002 of insider trading after she dumped her stock in a company called Imclone the day before bad news from the FDA caused the stock's price to plummet. She and her broker Peter Bacanovic ultimately were not indicted for insider trading, but were convicted of multiple counts of false statements, perjury, and obstruction of justice for concocting a phony story about why she sold the stock and then lying to the FBI and SEC.

And Dennis Hastert, the former U.S. Speaker of the House, allegedly had sexual contact with students decades ago while he was working as a high school teacher and coach. He was recently indicted not for any sexual misconduct but for lying to the FBI about his apparent hush-money payments to one of his victims and for structuring his bank transactions to conceal those payments. (Hastert recently pleaded guilty to one count of structuring bank transactions and is awaiting sentencing.)

It’s a legal maxim, particularly in the post-Watergate era, that often the cover-up is worse than the crime. It’s a flawed maxim, for two reasons. First, the cover-up itself might also be a crime. And second, what is being covered up does not have to be criminal - cover-up crimes can take place in an effort to conceal non-criminal conduct that is simply embarrassing or potentially damaging.

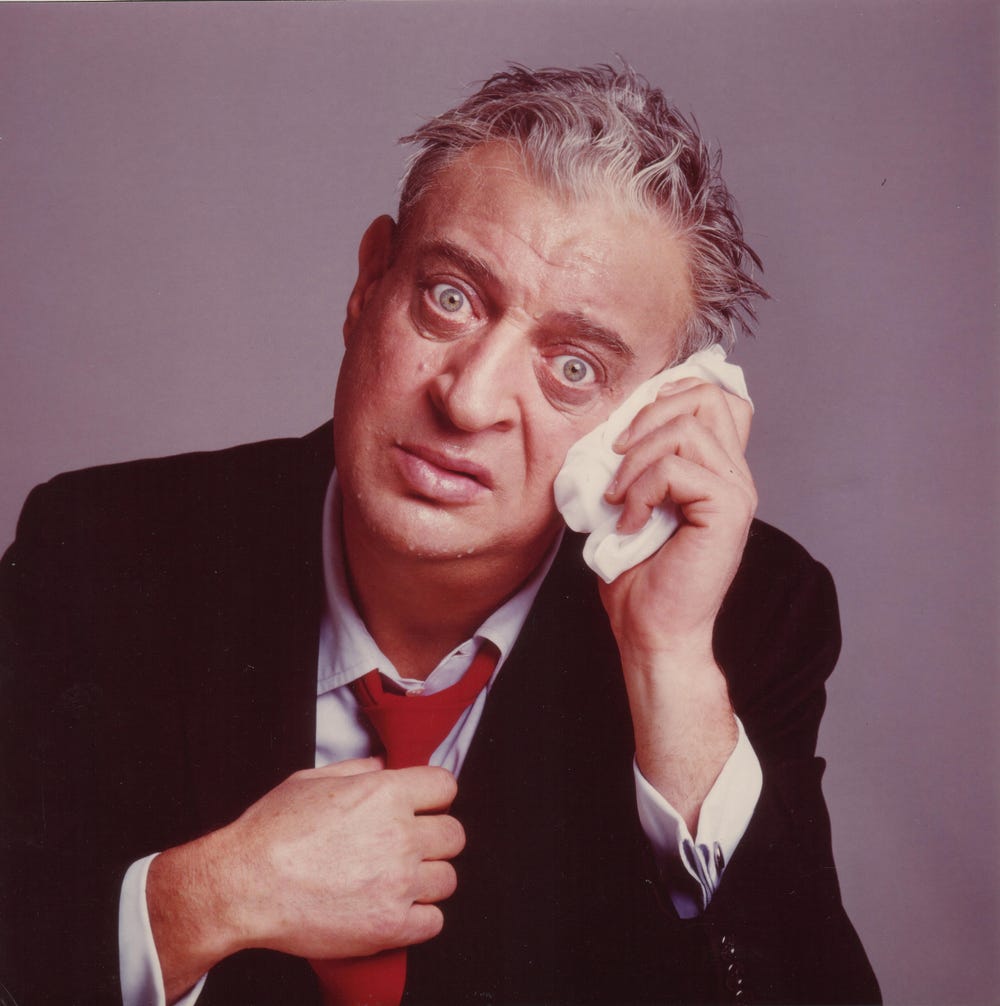

But cover-up crimes are the Rodney Dangerfield of the white collar world: they don’t get any respect. You frequently hear them derided as “gotcha” crimes or “process” crimes, or as something prosecutors charge only when they can’t “get” a defendant for anything else. There is a widespread perception that these crimes are somehow less serious than many other white collar offenses.

But the truth is that prosecution of cover-up crimes is vitally important to the proper functioning of the justice system. It’s time these crimes got the respect they deserve.

The Leading Cover-up Crimes

Perjury – 18 U.S.C. §§ 1621, 1623: Perjury, or lying under oath, is the classic cover-up crime. There are two principal federal statutes: 18 U.S.C. § 1623 applies only in federal judicial and grand jury proceedings, while 18 U.S.C. § 1621 applies in any proceeding where an oath is authorized by law, including Congressional hearings and investigations by agencies such as the SEC.

Perjury requires that the defendant was under oath, made a false statement about something material to the proceeding, and knew that it was false at the time. Mistakes or innocent failures of recollection are not perjury; it requires a knowing lie.

Perjury is the narrowest of the cover-up crimes because of the oath requirement, which sharply limits the types of proceedings in which it applies. It is also notoriously difficult to prosecute. Perjury requires strict proof that the defendant was deliberately lying and that there was no room for confusion, misunderstanding or ambiguity. Pinning down evasive witnesses is not easy. As a result, testimony that is unresponsive or even misleading may not be perjury because nothing is said that is provably false.

A well-known example of this occurred during the investigation of President Bill Clinton, when he denied under oath ever having “sexual relations” with Monica Lewinsky. It was later determined, of course, that the two did have a relationship that was sexual in nature. But the questioner’s convoluted definition of “sexual relations” coupled with a failure to pin Clinton down with follow-up questions resulted in sworn testimony that was potentially misleading but likely not perjury.

False Statements – 18 U.S.C. § 1001: The false statements statute is perjury’s more sweeping cousin, and broadly criminalizes lying to the government. The statement must be knowingly false, must be in a matter within the jurisdiction of one of the three branches of the federal government, and must be material, or potentially important. Most notably, there is no requirement that the statement be under oath.

False statements can also apply to defendants who do not actually lie, but who conceal material facts from the government through a trick, scheme or device when they were under a legal obligation to reveal those facts (such as a reporting requirement created by statute, for example).

Martha Stewart, Scooter Libby, and Dennis Hastert all were charged with false statements for lying to the FBI in unsworn interviews. Lies in government contracting documents, in reports to administrative agencies, in applications for government programs, and in any other communication with the federal government may potentially result in false statements charges.

Obstruction of Justice – 18 U.S.C. §§ 1503, 1505, 1512, 1519: A number of different statutes apply to obstruction of justice; I’ve listed only the principal ones. They differ in the types of proceedings to which they apply and in some other particulars, but also overlap a great deal. In general, obstruction of justice means the defendant knowingly and wrongfully endeavored to impair, obstruct or impede the due administration of justice in some proceeding.

Obstruction of justice covers a wide variety of conduct, including tampering with witnesses, threatening or injuring judges or jurors, and destroying, altering or concealing evidence. It may also apply to lying to investigators or in official proceedings with the intent to obstruct, and to that extent can overlap with both perjury and false statements. In the cases of Scooter Libby and Martha Stewart, for example, the defendants were charged with false statements for lying to investigators and were also charged with obstruction of justice for an overall pattern of conduct during the investigation that included, among other things, telling those lies.

Prosecution Priorities and Cover-up Crimes

Cases charging cover-up crimes are often met with a reaction that ranges from skepticism to outrage. When Barry Bonds was prosecuted for perjury and obstruction of justice, there was a lot of commentary suggesting that the case was just an attempt by the prosecutors to “get” Bonds for something trivial because they didn’t like him. When Hastert was recently indicted, some suggested the charges were not appropriate and that Hastert was being unfairly singled out. And even more than a decade after her trial, it’s not unusual to hear someone express outrage over the fact that Martha Stewart was prosecuted.

The sense that these are not serious crimes is widespread. I’ll never forget seeing a sitting U.S. Senator on cable news, when the Scooter Libby case was going on, saying something like, “If there are indictments, I hope it’s for a real crime, and that the prosecutors don’t just go after someone on some technicality like perjury.”

But prosecutors certainly don’t see cover-up crimes as mere technicalities or trivial offenses. These often-maligned charges play a number of important roles.

First, when included in a case with other charges, cover-up crimes may provide valuable evidence of criminal intent. In many white collar cases, proof of intent is the critical issue. It’s often pretty clear what happened and who did what; in a contracting fraud case, for example, the paper trail may easily establish that the defendant overbilled the government. The key issue is likely to be not what happened, but why: the defense will claim it was just a mistake or accounting oversight, not a fraud.

Cover-up crimes may provide powerful evidence of intent in such cases: people generally try to conceal their activities when they realize they’ve done something wrong. If the defendant in our contracting case shredded documents when they were subpoenaed, or tried to intimidate a witness, or lied to investigators, those cover-up crimes provide strong evidence of guilty knowledge. The argument is simple: if they thought they did nothing wrong, why did they try to cover it up?

In other cases, cover-up crimes may serve the interest of justice by ensuring that defendants who engaged in criminal conduct that cannot now be prosecuted are still punished. For example, a defendant may have committed crimes that are now outside the statute of limitations, a key witness may have died making prosecution impossible, or some other critical piece of evidence may be unavailable. If during an investigation of that other criminal activity the defendant engages in a cover-up crime, bringing those charges can ensure that the defendant does not entirely escape the criminal consequences of the earlier activity.

Charges in such a case do not unfairly circumvent the statute of limitations. The defendant is not being charged for the original misconduct. But the cover-up crime can be seen as part of an ongoing course of conduct that includes the earlier bad acts; without those acts, there would be nothing to cover up. It’s perfectly appropriate to hold the defendant accountable for the cover-up that arises from earlier misconduct that cannot now be punished -- particularly when, as in the Hastert case, for example, that prior misconduct was particularly egregious.

But more fundamentally, even when such considerations are not in play, pursuing cover-up charges plays a crucial role in the criminal justice system. Prosecuting such crimes is important because these offenses strike at the very foundation of the justice system.

The justice system, of course, depends upon the ability of finders of fact to receive all relevant and appropriate information necessary to decide a particular case. Cover-up crimes undermine that ability. If witnesses lie in the grand jury, lie on the witness stand, destroy evidence, tamper with witnesses, lie to investigators, or otherwise interfere with the due administration of justice, there must be consequences. If not, such behavior becomes the logical choice of anyone who has some reason to fear the truth.

Prosecution of cover-up crimes, by seeking to deter such behavior, preserves the fundamental operation of the justice system itself. If these crimes took place with impunity it would become impossible to investigate or prosecute anything effectively, whether white collar crime, violent crime, or terrorism. The effective functioning of the justice system depends upon people telling the truth and complying with the system's lawful demands -- and knowing they will pay a price if they do otherwise.

You can bet that every CEO knows what happened to Martha Stewart when she tried to lie her way through an SEC and FBI inquiry. Every government official knows what happened to Scooter Libby when he tried to obstruct an FBI investigation at the highest levels of government and lied about it in the grand jury. Such prosecutions can have a tremendous deterrent effect, and for that reason are tremendously important.

These crimes are not mere technicalities; they seek to preserve those aspects of our justice system upon which all else rests. That’s why prosecutors, who make their living within the justice system and working to further its goals, take these crimes so seriously, even if others do not always agree. And that’s why prosecution of cover-up crimes deserves a little more respect.