Mueller Monday: Breaking Down the Charges and Looking Ahead

This past Monday Special Counsel Robert Mueller unveiled the first criminal charges in his ongoing probe of potential ties between Russia and the Trump campaign. Word of an impending indictment leaked last Friday, and Washington was buzzing all weekend about who might be the target. On what the Internet quickly dubbed #MuellerMonday, prosecutors unsealed a twelve-count indictment charging former Trump campaign manager Paul Manafort and his associate Richard Gates. The charges against Manafort were not a great surprise. The FBI had executed a search warrant at his house last July, and there were reports he had been told to expect an indictment. But Mueller’s other announcement was unexpected: he also unsealed a guilty plea by a former foreign policy advisor to the Trump campaign, George Papadopoulos. It turns out Papadopoulos was arrested last July, was charged under seal, and has been cooperating with Mueller’s office. The charges indicate that Mueller’s team is moving forward aggressively and effectively. There are likely many more shoes to drop before he is done. And with Monday's moves he’s sent an unmistakable message to others who may have been involved in any criminal conduct.

Special Counsel Robert S. Mueller, III

Breaking Down the Charges

Manafort and Gates Overview

The indictment encompasses activity from 2006 to 2017. During that time Manafort ran two different political consulting firms. Gates worked for Manafort and the indictment identifies him as Manafort’s “right hand man.” Beginning in 2006, various pro-Russia political parties and individuals in Ukraine hired Manafort's firms for lobbying and political consulting, and that work continued for a decade. The defendants allegedly concealed this work from the federal government by failing to register as foreign agents as required. The defendants used an entity called the European Centre for a Modern Ukraine (the Centre) to retain other lobbying firms in the United States. The Centre was in fact controlled by political leaders in Ukraine working with the defendants. Using the Centre as a front allowed the defendants to distance themselves from the Ukrainian work and conceal it from the government. Manafort and Gates also allegedly concealed the money they were earning from Ukraine by routing that money through a large number of corporations, partnerships, and bank accounts, including foreign corporations and accounts established in Cyprus, Saint Vincent & the Grenadines, and the Seychelles. To hide the existence of these foreign bank accounts they allegedly failed to report their control over those accounts to the federal government as required, both on their income tax returns and by separate required filings. In addition, the defendants allegedly used nearly three dozen different offshore entities, primarily located in Cyprus, to wire millions of dollars into the United States to pay for goods, services, and real estate for themselves. None of this money was reported as income by the defendants or by Manafort’s companies. The indictment includes a seven-page detailed list of these payments, which included more than $5 million to a home improvement company in the Hamptons, nearly $1 million to an antique rug store, more than $800,000 to landscape companies in the Hamptons, and more than $1.3 million to clothing stores.

Paul Manafort

Criminal Charges Against Paul Manafort and Richard Gates

Count One: Conspiracy, 18 U.S.C. 371 Count one charges both defendants with conspiracy under 18 U.S.C. 371. This is an overarching charge that encompasses the entire scheme from 2006 to 2017. The federal conspiracy statute prohibits conspiracies to defraud the United States and conspiracies to commit an offense against the United States. The indictment charges both. A conspiracy to defraud the United States includes an agreement to impair, obstruct, or impede the lawful functions of the U.S. government. The indictment charges that the defendants’ activities impaired and obstructed the lawful functions of the Department of Justice (which is charged with monitoring the activities of foreign agents) and the Department of the Treasury (which includes the Internal Revenue Service). The indictment also charges the defendants with conspiracy to commit offenses against the United States, which means a conspiracy to commit any federal crime. It alleges that they conspired to commit the federal crimes contained in the subsequent counts of the indictment. This is a pretty common structure for a white collar crime indictment. The conspiracy charge up front tells the story of the entire criminal scheme, and it is followed by individual counts of the crimes the defendants allegedly conspired to commit. Conspiracy under 18 U.S.C. 371 is punishable by a maximum of five years in prison. Count Two: Conspiracy to Launder Money, 18 U.S.C. 1956(h) Count two charges that by moving millions of dollars through their various partnerships, corporations, and foreign accounts, the defendants conspired to commit money laundering. Several different money laundering theories are charged as the objects of the conspiracy. The first is that the defendants transferred funds across international borders in order to promote criminal activity, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1956(a)(2)(A). The second is that the defendants engaged in financial transactions in criminal proceeds with the intent to evade income taxes, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1956(a)(1)(A)(ii), and knowing that those transactions were designed to conceal and disguise the source, ownership, and control of the proceeds, in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1956(a)(1)(B)(i). Put more simply, this charge focuses on the defendants’ use of their extensive network of foreign companies and bank accounts to promote their business, conceal their activities and sources of income from the government, and avoid paying taxes. The money laundering conspiracy is the most serious charge in the indictment, carrying a maximum penalty of twenty years in prison. Counts Three to Nine: Failure to File Reports of Foreign Bank Accounts, 31 U.S.C. 5314, 5322(b) The Bank Secrecy Act requires U.S. citizens to file reports with the U.S. Treasury concerning any foreign bank accounts they own or have signatory authority over if the balance exceeds $10,000 at any time during the year. These are called foreign bank account reports, or “FBARs.” Willfully failing to file a required FBAR while engaged in other criminal activity is a ten-year felony. Counts three to six charge Manafort with failing to file a required FBAR for the years 2011, 2012, 2013 and 2014, thus concealing his interest in multiple foreign bank accounts. Counts seven to nine charge Gates with the same offense for the years 2011, 2012, and 2013. Count Ten: Failure to Register as Foreign Agent, 22 U.S.C. 612, 618 The Foreign Agents Registration Act (FARA) requires persons who engage in lobbying or public relations work in the United States on behalf of a foreign principal to file detailed reports, under oath, with the Department of Justice. The reports must include the identity of the principal and the nature of the work being done. Count ten charges that between 2008 and 2014 both defendants failed to register as required by FARA for their work on behalf of the Ukrainian government and Ukrainian officials. The FARA violation is punishable by up to five years in prison. Count Eleven: False and Misleading FARA statements, 22 U.S.C. 612, 618 FARA also makes it a crime to make false or misleading statements in connection with a FARA report. Count eleven charges that in November 2016 and February 2017, both defendants filed documents with the Department of Justice that contained false and misleading statements about their work on behalf of Ukraine. In particular, it alleges that they lied about their own role in the lobbying and falsely claimed that all such work was actually coordinated by the Centre. Count Twelve: False Statements, 18 U.S.C. 1001 Count twelve charges essentially the same false and misleading FARA statements alleged in count eleven but charges them under a different statute, 18 U.S.C. 1001, the general false statements statute. That statute criminalizes any material false statement made in a matter within the jurisdiction of one of the branches of the federal government. It is also punishable by up to five years in prison. Summary: Manafort: Charged in counts 1-6 and 10-12, maximum statutory exposure 80 years. Gates: Charged in counts 1-2 and 7-12, maximum statutory exposure 70 years.

George Papadopoulos

Criminal Charges Against George Papadopoulos

Papadopoulos pleaded guilty under seal to one count of lying to the FBI in violation of 18 U.S.C. 1001, false statements. His maximum exposure is five years, although his plea agreement indicates he may be sentenced to as little as 0-6 months. The plea documents contain a statement of facts, which Papadopoulos has admitted as true. He admits he lied to the FBI during an interview on January 27, 2017 about his contacts with Russian individuals while working on the campaign. (Note that this interview was only a week after President Trump was inaugurated, and took place four months before Mueller was appointed Special Counsel.) During that interview Papadopoulos falsely downplayed his interactions with Russian individuals and claimed those interactions took place prior to his work on the campaign. The plea documents contain a detailed timeline showing that Papadopoulos in fact had extensive contacts with Russian individuals while working on the campaign. These included Russian operatives with shadowy nicknames such as the “professor” and a “female Russian national” who claimed she was related to Vladimir Putin. Papadopoulos had repeated contacts with these individuals, trying to broker meetings between Russian government officials and members of the Trump campaign. They reportedly told Papadopoulos that Russia could offer “dirt” on Hillary Clinton and that they had “thousands of emails.” At one point the “female Russian national” told him, “We are all very excited by the possibility of a good relationship with Mr. Trump.” Papadopoulos repeatedly advised other members of the Trump campaign (including an unidentified “senior policy advisor” and “high-ranking campaign official”) of his progress in his contacts with the Russians, and was encouraged to keep pursuing them. These included communications about the Russia ministry of foreign affair’s interest in a possible meeting with Trump in Russia. After repeated communications about a possible “off the record” meeting with Russian officials, a “campaign supervisor” encouraged Papadopoulos to make the trip, if feasible. The proposed trip never actually took place. Although the Papadopoulos plea contains detailed information about his efforts to work with Russian nationals on behalf of the campaign, he is not actually charged with any crimes related to his Russian contacts. Instead, he pled guilty to lying to the FBI when interviewed about those contacts.

What to Expect Going Forward

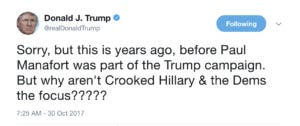

The release of both sets of charges on the same day was a shrewd strategic move by Mueller. Manafort, who apparently has refused to cooperate, ends up indicted and potentially facing a decade or more in prison. Papadopoulos, who chose to cooperate and plead guilty, faces a single, relatively minor felony charge and may avoid jail altogether. The message to future witnesses is clear: be like George, not like Paul. President Trump himself was quick to point out that the charges against Manafort primarily involve conduct that took place before he was involved in the campaign:

It's true that most -- though not all -- of the alleged crimes in the indictment predate Manafort's work on the campaign, but that's largely beside the point. Mueller’s purpose, in addition to pursuing criminal charges that are fully justified in and of themselves, is to pressure Manafort into cooperating in the broader investigation. The indictment gives him the leverage to do that. As a campaign manager who also had extensive ties to Russia, Manafort may be uniquely situated to provide information central to Mueller’s investigation. He will now be under tremendous pressure to cooperate and share that information to help himself out in his own case. The nature of the charges is particularly bad news for Manafort and Gates. These financial charges are tough to defend against. They don’t depend on a lot of nuance or witness credibility. The indictment spells out the paper trail in excruciating detail, and the jury needs only to follow the money. There are not many obvious defenses that leap off the pages of the indictment. Manafort and Gates also need to be aware that this could be just the beginning. The allegations in the indictment suggest other potential charges that have not yet been filed, including tax crimes and bank fraud. Mueller’s team always has the option of bringing a superseding indictment to add more charges. It's also possible the New York Attorney General could file state charges -- and those would be outside the reach of President Trump's pardon power. The case against Manafort and Gates will move forward now in the ordinary course, with motions, discovery, and potentially a trial. It will occupy the time of a couple of members of Mueller's team, but the rest will continue to move the broader investigation forward. Either or both of the defendants could decide to plead guilty at any time. Presumably they will have discussions with the Special Counsel’s office about possible cooperation -- a prospect that has to make others involved in the campaign extremely uneasy.

A "Proactive Cooperator"

As for Papadopoulos, there has been a lot of speculation about what his cooperation over the past few months may have entailed. It’s all guesswork for now – but keep in mind that Mueller had him charged under seal, to keep it a secret. One reason to do that would be if Papadopoulos was covertly assisting in the investigation. Speculation that this might have happened was further fueled by a paragraph in his plea agreement referring to him as a “proactive cooperator.” Whether Papadopoulos actually worked with the FBI will be revealed in due course. It’s certainly possible that investigators could have had him make recorded phone calls, or arrange meetings with other targets while wearing a wire, to talk about the events under investigation. Or his cooperation may have simply involved providing testimony and documents about past conduct. The other important aspect of Papadopoulos’s case is the detailed timeline and statement of facts in support of his plea. Although it contains pseudonyms like “senior campaign official,” everyone knows that Bob Mueller’s team knows who those people are. Investigators appear to know in great detail what happened during the campaign. And if future witnesses try to come in and lie to them, they will find themselves in the same boat as Papadopoulos. Once again, the strength of the charges and the amount of detail in the documents sends a clear signal that these investigators aren’t playing around and won't be easily fooled. The documents in Papadopoulos's case don't prove that collusion with Russia took place -- although to steal a phrase from John Dickerson, they certainly establish that the Trump campaign was "collusion curious." Whether any collusion or attempted collusion that did take place actually amounts to a crime is yet another question. But the guilty plea does make it clear that Mueller's team is deep into examining the operations of the campaign and potential ties to Russia, and already knows a great deal. Finally, the release of Papadopoulos’s documents further highlights the jeopardy in which Manafort finds himself. There is widespread agreement that the “senior campaign official” referred to in Papadopoulos’s plea is Manafort, who is now on notice that Mueller has an insider telling him all about the campaign, Russia, and the role played by Manafort and others. If Manafort ends up meeting with Mueller's team about those issues, he knows he can't get away with hiding the ball. Mueller’s team appears to be pursuing a classic investigative strategy of building cases against lower-level players, persuading the to “flip” and cooperate, and moving up the ladder. Whether Manafort flips or not remains to be seen, but regardless, there’s every reason to believe the Special Counsel is just getting started.

Like this post? Click here to join the Sidebars mailing list