Presidential Immunity

SCOTUS throws Trump a lifeline

Today the Supreme Court decided the Trump presidential immunity case. The vote was 6-3, along the usual party lines. The Court held that the former president is entitled to immunity for at least some official acts related to the events that led up to the January 6 Capitol riot. It remanded the case to Judge Chutkan to determine which allegations in the indictment may be the subject of a prosecution and which are protected under the immunity standards announced by the Court. That almost certainly means there will be no trial in the D.C. case before the November election.

I thought the Court was likely to hold that some presidential actions may be entitled to immunity, but the Court went further than I expected. This decision represents a profound change in our constitutional structure and in the relationship of the president to the rest of the people. For the first time, the president is indeed above the law, at least in some cases.

It’s going to take some time to sort through all of the implications of the Court’s decision; this will just be a quick overview. When it comes to the D.C. prosecution of Trump for the events of January 6, my initial impression is that it will survive for the most part, for reasons I’ll explain below. I’m more concerned about the long-term implications of the decision, particularly if someone like Trump is elected president again.

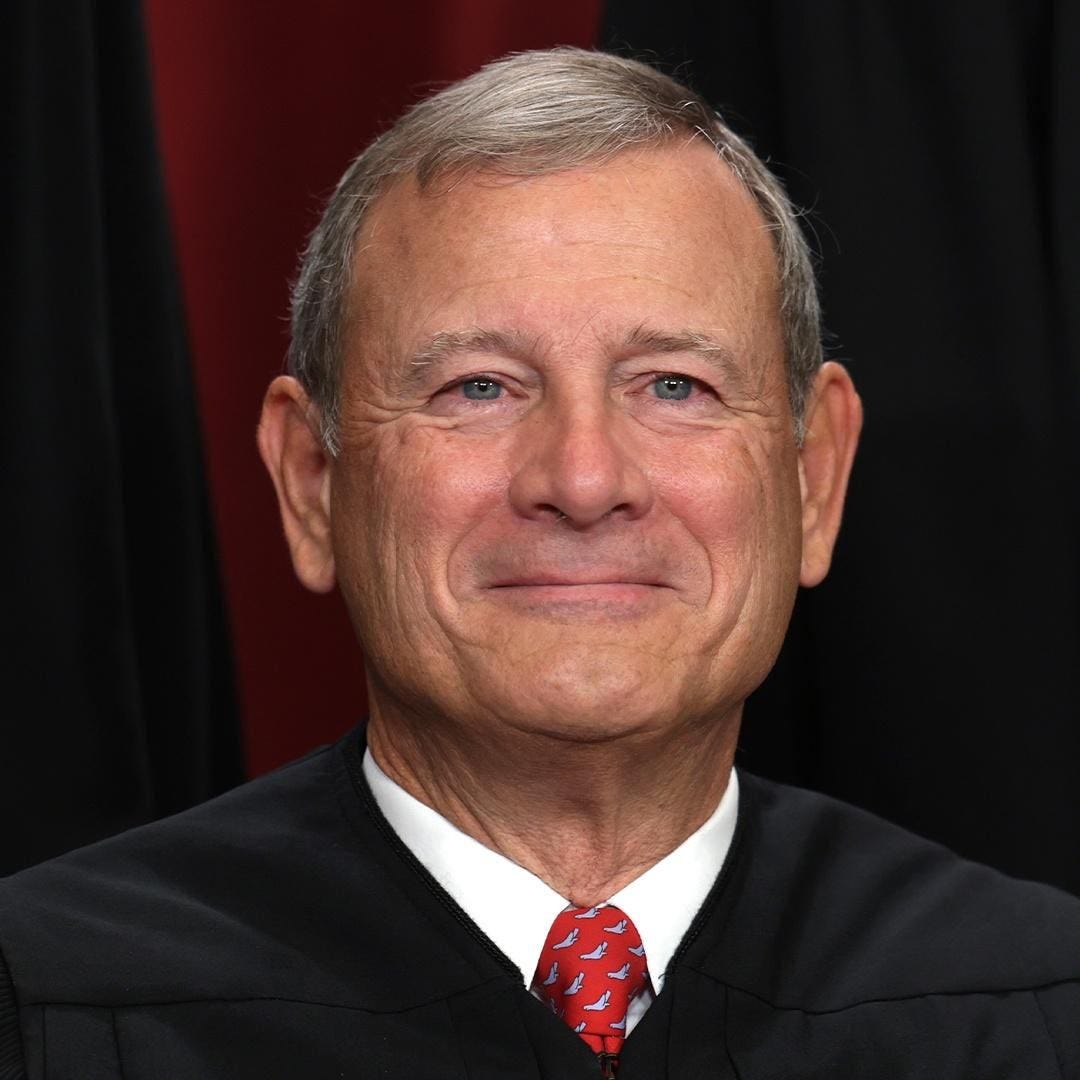

Chief Justice John Roberts

Presidential Immunity: Three Buckets

The majority opinion by Chief Justice Roberts holds that although there is no presidential immunity specified in the Constitution, the requirement for that immunity arises from the separation of powers and the nature of Executive authority. The president must be free to take “bold and unhesitating action” on behalf of the country without fear that a future political rival will criminally prosecute him for those actions. Absent immunity, the Court held, there would be a risk of “an Executive Branch that cannibalizes itself, with each successive President free to prosecute his predecessors, yet unable to boldly and fearlessly carry out his duties for fear that he may be next.”

The majority identified three different relevant categories of executive action:

Acts that are within the president’s “exclusive sphere of constitutional authority” and are expressly assigned to the president by the Constitution. These include the power to command the military, to grant pardons, and to appoint ambassadors and other officers of the United States. These core presidential acts, the Court held, are entitled to absolute immunity from criminal prosecution - but the opinion is not very clear on the precise scope of these core duties or how that is to be determined.

Other “official acts” that the president carries out within the scope of his duties but that are not part of the core powers exclusively delegated to the presidency. The Court held that a president is entitled to at least presumptive immunity for such official acts that are within the outer perimeter of his official responsibility. This presumption can be rebutted if the government can show that a criminal prosecution would pose no “dangers of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.”

Unofficial acts, for which there is no immunity.

The key question, then, is whether the allegations in the indictment seek to prosecute “official acts.” These questions were not addressed in the lower courts, which denied immunity under any circumstances. As if to push back on the criticism of its own slow pace in resolving the case, the Court criticized the lower courts for their haste: “Despite the unprecedented nature of this case, and the very significant constitutional questions that it raises, the lower courts rendered their decisions on a highly expedited basis.”

For the most part, the case now goes back to Judge Chutkan for briefing and probably hearings, so she can decide which allegations in the indictment involve official acts and are therefore immune. The Court did make a few preliminary determinations of its own, however:

The Court held that the allegations that Trump tried to leverage the Justice Department and pressure the Attorney General to investigate allegations of voter fraud were entitled to absolute immunity. The Court said these acts implicated exclusive executive power to enforce the laws, conduct investigations, and hire and fire the officers in his administration.

The Court also held that Trump’s efforts to pressure Vice President Mike Pence and influence him regarding the electoral vote count were presumptively official acts, given the nature of the vice president’s role. However, the government may be able to rebut the presumption that those efforts were privileged by showing that they implicated no official duties of the president, who has no role in the electoral vote count. These allegations fall into the “second bucket” discussed above.

As to the other allegations in the indictment, including pressuring state officials to overturn their election results, the fake electors scheme, and the speech at the Ellipse, the trial judge in the first instance will need to develop a record and determine whether those actions were official or unofficial.

The Court held that, in determining whether an action was official or unofficial, the president’s motives may not be considered. That kind of inquiry, the Court said, would intrude too deeply on the executive’s responsibilities by allowing the other branches to second-guess any presidential action by simply alleging an improper motive.

The Court also rejected the government’s argument that even if some acts were official and could not be the basis of a prosecution, evidence of those acts could still be used to prove things such as the president’s intent or knowledge relative to other charges. The majority said allowing that use would “eviscerate” the immunity it had just recognized by allowing prosecutors to do indirectly what they may not do directly.

Other Opinions

Justice Thomas wrote a concurrence arguing that the appointment of special counsel Jack Smith was unlawful. That argument has been made and rejected in other special counsel cases and is currently the subject of a motion Trump has filed in his Florida prosecution. None of the other Justices joined his opinion.

Justice Barrett wrote a concurrence agreeing with most of the majority opinion but disagreeing that a president’s immune official acts could not be used for other purposes, such as to prove knowledge or notice. She agreed with the dissent that the “Constitution does not require blinding juries to the circumstances surrounding conduct for which Presidents can be held liable.” She also would have made it clear that there is no absolute immunity for official acts outside core presidential responsibilities. She mentioned several allegations in the indictment, such as Trump speaking with state officials about the election or organizing slates of fake electors, and said she saw no reasonable argument that those were official acts entitled to immunity.

Justice Sotomayor filed a dissent joined by Justices Kagan and Jackson. She argued that the majority’s decision had no basis in the text of the Constitution and was fundamentally inconsistent with our constitutional history. She said the majority had overstated the risks of potential prosecution and the ability of those risks to chill decisive executive action. A far greater risk, she argued, is a president who feels unconstrained by the criminal law: “I am deeply troubled by the idea, inherent in the majority’s opinion, that our Nation loses something valuable when the President is forced to operate within the confines of federal criminal law.” She concluded her opinion:

Never in the history of our Republic has a President had reason to believe that he would be immune from criminal prosecution if he used the trappings of his office to violate the criminal law. Moving forward, however, all former Presidents will be cloaked in such immunity. If the occupant of that office misuses official power for personal gain, the criminal law that the rest of us must abide will not provide a backstop.

With fear for our democracy, I dissent.

Justice Jackson also filed her own dissenting opinion.

What Happens Now

The case will go back to Judge Chutkan for the findings that the Court directed. She will have to determine whether the allegations in the indictment involve official presidential acts. For those that do, she will have to determine whether prosecution based on those acts would impose a “danger of intrusion on the authority and functions of the Executive Branch.” If so, they are immune and may not be part of the case; if not, then the prosecution based on those acts may move forward.

Based on the Court’s opinion, the allegations about Trump pressuring the Justice Department and threatening to replace the Attorney General appear to be out. The allegations about pressuring Mike Pence are presumptively immune, but prosecutors should have a good shot at demonstrating that when it comes to the vice president’s role in counting electoral votes, the president has no responsibilities and those are not official acts.

Almost all of the other allegations, including the pressure campaign on state officials and the fake electors scheme, should be found to be not official. As Justice Barrett suggested, these were private actions in areas where the president has no official responsibilities.

The speech at the Ellipse, where Trump exhorted the mob and then sent them to the Capitol, may be a closer call. The majority said that when the president speaks to the public, that usually will fall within the perimeter of his official responsibilities. However, the Court did note that there may be contexts “in which the President, notwithstanding the prominence of his position, speaks in an unofficial capacity—perhaps as a candidate for office or party leader.”

I do see one possible silver lining: a key goal of having a trial before the election was to inform (or remind) the voting public of Trump’s actions involving the attempt to overturn the election. Now it’s clear we won’t have a jury verdict on those allegations by November. However, Judge Chutkan could hold extensive evidentiary hearings on the allegations in the indictment, in order to make the required determinations about official acts. Those could start relatively soon, and would also serve the purpose of informing the voters about the allegations in the indictment, even if the case can’t be concluded prior to the election.

The Blassingame Case

There is a good precedent for the government as Judge Chutkan begins this task. In Blassingame v. Trump, law enforcement officers and members of Congress who were injured during the Capitol riot sued Trump for damages. Trump argued he was immune from the civil lawsuits under the Supreme Court’s Nixon v. Fitzgerald case. That case held that a president is immune from civil damages for actions within the outer perimeter of this official responsibilities - the same standard the Supreme Court has now adopted for criminal liability.

The D.C. Circuit in Blassingame distinguished between acts of a president as president and his acts as a candidate: “When a first-term President opts to seek a second term, his campaign to win re-election is not an official presidential act.” It held that Trump is not immune from liability for his actions leading up to and on January 6 because his actions were in “his personal capacity as presidential candidate, not in his official capacity as sitting President.”

Many of the same actions at issue in Blassingame, including pressuring state and local officials and the rally and speech at the Ellipse, form the basis of the criminal indictment. I expect Judge Chutkan will follow a similar approach and conclude that most of the actions alleged in the indictment are private acts of Trump as a candidate, not official acts of the president. As such, they should not be entitled to immunity under today’s decision.

In the end I think most of the indictment will survive, and Trump will still face trial in the D.C. case — assuming he does not win re-election and shut down the prosecution.

Effect on Other Trump Prosecutions

The New York state case, where Trump has already been convicted, should not be affected by this decision. The actions in that case almost all took place before Trump was president and there’s no plausible argument they were official acts entitled to immunity.

The Florida federal case should not be affected either. There all the relevant criminal acts — retaining the classified materials, refusing to return them, and obstructing justice — took place after Trump left office. Again, there is no plausible way to argue these were official acts of the president. I do expect Trump’s lawyers will try to argue that his initial decision to take the documents, while he was still president, was an official act and that somehow entitles his later actions to immunity. I don’t think that passes the laugh test - but with Judge Cannon, you never know. At a minimum, she might hold hearings and take several months to consider the matter.

If the Georgia case ever gets moving again, it is going to face most of the same issues as the D.C. case. That indictment involves all of the same allegations related to January 6. Judge McAfee will have to determine which allegations involve official acts that might be subject to presidential immunity. Perhaps by the time that happens, we will have some findings by Judge Chutkan that he can look to for guidance.

Seal Team Six

Remember that Seal Team 6 hypo? During arguments in the D.C. Circuit, Judge Pan asked Trump’s lawyers whether a president could order Seal Team 6 to kill a political rival and then claim presidential immunity. When Trump’s attorneys answered that under some circumstances that might be an immune official act, most people thought that was bonkers. It was seen as the hypo that exposed just how crazy and radical Trump’s position was and ensured that he would not prevail.

Well, under this decision, I don’t see any way that act would not be entitled to absolute immunity. Command of the military is one of those areas within the president’s “exclusive sphere of constitutional authority” - the first bucket discussed above. Such actions now can’t be challenged, no matter how corrupt. I think Justice Sotomayor is therefore correct to say that this act would be completely immune.

It seems to me the same would be true if a president ordered the military to stage a coup and help him remain in office after losing an election. Once again, it appears that anything involving commanding the armed forces would be completely immune.

Or consider the Court’s holding that the president enjoys absolute immunity when dealing with the attorney general about potential criminal investigations or prosecutions. That appears to mean that a president could order his attorney general to prosecute or jail political rivals or other enemies with no factual basis, and that conduct would be completely immune from criminal prosecution.

That’s why I said up front that I’m more worried about the implications of this decision for future presidents than I am about its effect on the Trump prosecutions. A president who knows he can cloak his official actions in criminal immunity can easily become a tyrant.

One of the major legal guardrails to control presidential behavior has just been removed. Now more than ever, character is going to matter when we elect a president.

Best analysis I have read thus far. That said, I am confused and troubled by the notion that a president could engage in a core presidential act of communicating with the Secretary of Defense (by way of example), order the SecDef to have SEAL TEAM 6 take out his rival, and this not be an unlawful act. Murder is prohibited in the UCMJ, in certain federal situations, and all states. In other words, the president would be engaging in a lawful act for an unlawful purpose. How could the president be immune from criminal charges in this instance?

The POTUS now has the authority to invoke the Insurrection Act, deploy US troops into American cites, and order them to fire into a crowd of protesters. And he would be absolutely immune.