The Search at Mar-a-Lago

On August 8, the FBI executed a search warrant at Donald Trump’s residence at his Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida. The search followed more than a year of efforts to get Trump to return government documents he had taken with him when he left the White House in January 2021. In the search, agents recovered a large number of classified materials that had been improperly kept at Trump’s residence.

The government’s evaluation of any potential damage to national security resulting from Trump’s retention of these documents is ongoing, as is the criminal investigation into the handling of the documents. But the implications of the search are clear: of all the investigations swirling around the former president, this may be the one that most squarely places him in legal jeopardy.

Events Leading Up to the Search at Mar-a-Lago

The National Archives and Records Administration (NARA) has been trying to recover official government records from Trump ever since he left office in January of 2021, amid news reports of moving vans taking documents to Mar-a-Lago.

After a year of negotiations, Trump turned over 15 boxes of documents to NARA in January of 2022. At the time, he and his representatives did not claim any executive privilege related to the documents. Nor did they claim that Trump had declassified any documents.

When NARA reviewed the so-called “fifteen boxes,” they found a lot of classified material mixed in with other papers and personal items. As a result, in May they referred the matter to the Department of Justice for an investigation into the mishandling of classified information. When DOJ reviewed the boxes, it found 184 classified documents, including 25 that were marked Top Secret.

On May 11, believing Trump still had additional documents, DOJ issued a grand jury subpoena for any classified materials at Mar-a-Lago. On June 3, the president’s representatives met with investigators and turned over a single Redweld folder of documents in response to the subpoena. Once again, they did not claim that the documents had been declassified; in fact, they treated them as sensitive materials by wrapping the folder in tape and sealing it.

Trump’s representatives gave the agents a certification, signed by one of Trump’s attorneys, that they had made a “diligent search” and that this was all the classified material that remained. They also showed the agents a storage room where there were additional boxes of documents, but refused to allow the agents to open the boxes to verify that they did not contain any classified materials. The folder they turned over contained 38 more classified documents, including 17 marked Top Secret.

Following the June 3 meeting, the FBI reportedly developed “multiple sources of information” that there were still more documents that had not been turned over. They also developed evidence that “government records were likely concealed and removed from the Storage Room and that efforts were likely taken to obstruct the government’s investigation.”

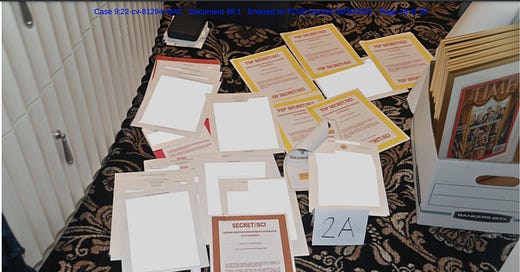

On August 5, DOJ applied for the search warrant, and it executed the warrant on August 8. They recovered 38 boxes, containers, or other items of evidence. Thirteen of them contained classified material. Some of them were extremely sensitive and classified at high levels such as SCI (Sensitive Compartmented Information).

As the government noted in an August 30 pleading, “That the FBI, in a matter of hours, recovered twice as many documents with classification markings as the ‘diligent search’ that the former President’s counsel and other representatives had weeks to perform calls into serious question the representations made in the June 3 certification and casts doubt on the extent of cooperation in this matter.”

The Criminal Statutes at Issue

The government cited three different criminal statutes in the search warrant, alleging there was probable cause to believe that evidence of those crimes would be found at Mar-a-Lago. These crimes potentially were committed not only by Trump himself, but also by some of his staff or attorneys who were involved with the documents.

18 U.S.C. § 793

The first statute referenced, Title 18 U.S.C. § 793, is part of the Espionage Act of 1917. It has a few different subsections, and the search warrant doesn’t specify which ones the government is focused on. Subsection (e) makes it a crime to be in unauthorized possession of documents or other information “relating to the national defense” with reason to believe that the information could be used to injure the United States or help a foreign nation, and to willfully retain that information and fail to deliver it to the government official entitled to receive it.

Subsection (f) makes it a crime for someone who is otherwise authorized to have national defense information to allow it to be removed from its proper place of custody through gross negligence, or after learning that it has been so removed, to fail to report it.

Both subsections (e) and (f) are ten-year felonies.

Information related to the national defense is broadly construed under this statute. Material that was important enough to be classified, particularly at the higher levels of some of the materials seized at Mar-a-Lago, would likely be considered national defense information.

Under this section the alleged crime is straightforward: Trump and his associates removed national defense information from its proper location, retained it, and failed to turn it over when it was requested by the proper government officials.

18 U.S.C. § 2071

This statute applies to anyone who “willfully and unlawfully” conceals, removes, or carries away any record or document, or other thing, “filed or deposited with any clerk or officer of any court of the United States, or in any public office.” It’s a three-year felony.

The “filed or deposited with” language has been interpreted broadly. The statute basically applies to any government documents that are supposed to be maintained by some public office, even if they haven’t been formally “filed.” Presidential records that are supposed to be maintained by the National Archives would fall into that category, and classified information certainly would as well.

Once again, the nature of the allegation here would be straightforward: Trump removed documents meant to be maintained at NARA or in other government offices and then concealed them when the government tried to get them back.

18 U.S.C. § 1519

This is an obstruction of justice statute. It applies to anyone who “knowingly alters, destroys, mutilates, conceals, covers up, falsifies, or makes a false entry in any record, document, or tangible object” with the intent to impede a federal investigation or the proper administration of any matter within the federal government’s jurisdiction. The maximum penalty is twenty years in prison.

The allegation here would be that Trump or those working for him concealed the records with the intent to impede either the FBI investigation or the NARA efforts to recover and maintain the documents. Unlike other obstruction of justice statutes, this section applies to investigations and does not require a more formal proceeding such as a trial, grand jury, or Congressional proceeding.

This statute was the subject of one of the more bizarre Supreme Court decisions in recent years, Yates v. United States. In Yates a fishing captain was charged under § 1519 for throwing overboard undersized grouper that were evidence of a violation of fishing regulations. The Court ruled that a fish was not a “tangible object” within the meaning of this statute and that 1519 applies only to objects that contain information, such as computer drives. But that would not be an issues in this case, which clearly involves records and documents within the meaning of the statute.

18 U.S.C. § 1001

This statute, false statements, is not mentioned in the warrant paperwork, but it is suggested by the recitation of facts in the government papers. The statute prohibits knowingly making any materially false statement in any matter within the jurisdiction of the federal government. It's punishable by up to five years.

Recall that in June, Trump’s attorney represented in writing that all of the requested documents had been turned over and that a “diligent search” had been conducted for any additional classified documents. As the government noted in its August 30 filing, the fact that the FBI quickly found so many additional classified documents calls into question the veracity of this certification.

If the government develops evidence that the attorney, Trump himself, or others working for Trump knowingly made a false certification that all documents were turned over, that could implicate not only obstruction of justice but also the false statements statute.

Evidence of Trump’s Knowledge

In a criminal case, a potential defense for Trump presumably would have been a lack of knowledge about the documents. He might have tried to blame it all on his advisors, saying they must have mishandled his presidential records without his knowledge. But the evidence that has emerged so far has made such a defense basically impossible.

First is just the sheer volume of materials recovered. One might plausibly deny knowing about a stray document or two. But when we are talking about several dozen boxes of documents -- more than a dozen containing classified materials -- being kept in your home, it becomes much more difficult to claim you didn’t know they were there.

Another factor is where some of the documents were located. The government’s August 30 filing notes that some of the classified documents were found in Trump’s personal office, including in his desk drawer. A few were in a drawer that also contained Trump’s passports. If the classified materials are in your own desk and intermingled with your personal documents, it becomes much harder to deny that you knew about them.

The search warrant affidavit also noted that some of the classified materials turned over in January appeared to have Trump’s handwritten notes on them. This too would be evidence of Trump’s knowledge that he had the documents – although one issue might be proving when such notes were made. Trump could claim they were written while he was still in the White House.

Witnesses will also be important. The government may have developed witnesses who can testify about conversations with Trump concerning the presence of the documents and that he did not have a right to keep them at his home.

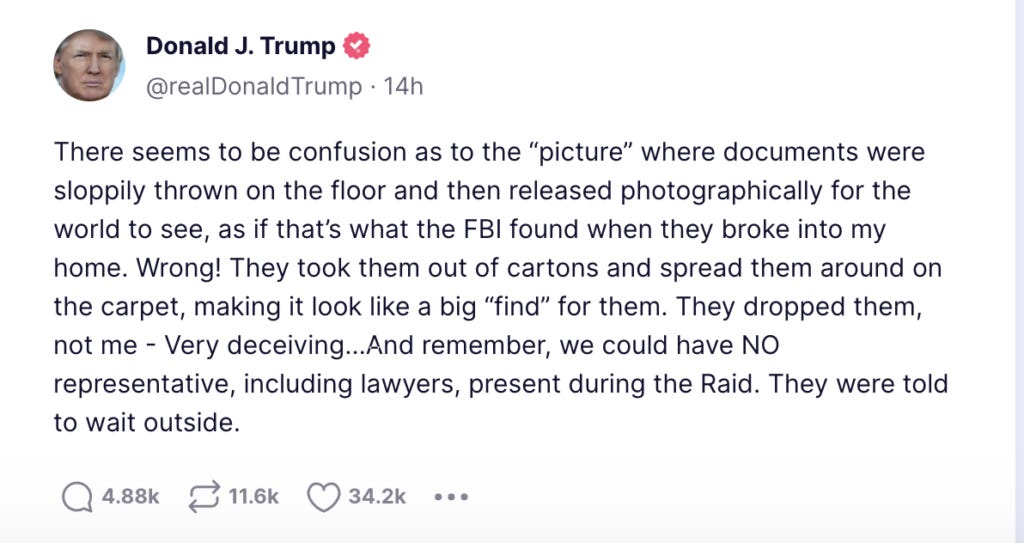

But the most damning evidence of Trump’s knowledge is his own words since the search took place. For example, after the search he said this on his platform Truth Social:

This statement admits he knew the documents were there, and that they were in “cartons.” Some of his allies on Fox News have tried to suggest that the FBI may have planted the documents, but this statement undermines any such claim.

Then there's this one:

The statement, “Lucky I declassified” is an admission not only that he knew he had the documents but that he knew they were classified, and implying that he knew it would be improper for him to have them if they were not declassified.

Trump’s inability to stay quiet must be maddening for his attorneys. He is undermining his own potential defenses.

The Declassification Argument

Trump and some of his allies have claimed there was no problem with him keeping the documents because Trump issued some kind of blanket declassification of all the documents before taking them. Presidents (although not former presidents) do have broad power to declassify information, but in this case that will not help Trump.

Legally, the declassification claim is irrelevant. If you review the criminal statutes discussed above, you will see that none of them require that the documents removed or concealed were classified. Trump, while still president, could have formally and officially declassified even the most sensitive information (although that would have been a gross dereliction of duty) and it would make no difference for purposes of the crimes being investigated.

Factually, there is no evidence of this purported declassification. The president can’t just wave a magic wand and declare something declassified; there would be paperwork and notations on the documents themselves. As far as we know, none of that exists. As the government has pointed out in its papers, at no time during the negotiations with NARA and in none of their court pleadings have Trump’s attorneys ever actually claimed that the documents were declassified.

The declassification argument is just a smokescreen. It didn’t happen, and even if it did, it wouldn’t matter. To be sure, the fact that the documents were classified is important in terms of the seriousness of the case. If the documents had consisted only of the guest lists for White House state dinners, there’s no way the government would have taken the dramatic step of executing a search warrant at a former president’s home. That the documents contained some of the country’s most sensitive information is an argument in favor of pursuing a criminal case – but it’s not a legal requirement for these potential crimes.

What Happens Next

It’s going to be very interesting to watch the developments in this case. There is some legal wrangling going on now over whether a court should appoint a Special Master to review the documents for any claims of executive privilege or attorney-client privilege, but that’s not going to make a big difference in the criminal case. Thanks to the president’s lawyers waiting two weeks to act, the government has already finished reviewing the documents and already knows what it has.

It will take some time for prosecutors and agents to analyze the recovered materials, complete the investigation, and evaluate any potential criminal charges. But it’s clear that this is an active, serious investigation that poses a real threat to the former president. And based on the government’s reference to witnesses and sources of information, someone inside the former president’s circle is talking – maybe multiple someones.

Trump’s attorneys are in a bit of a bind. Those who were involved in the negotiations with NARA and DOJ are likely going to have to withdraw from their representation of Trump. At a minimum, they are witnesses concerning the critical events in question. Depending on how the evidence develops, some of them could face legal jeopardy themselves. As someone joked on social media, maybe MAGA should stand for, “Make Attorneys Get Attorneys.”

There are almost certainly others, in addition to Trump himself, with criminal exposure here. It would not be surprising to see prosecutors build a case by persuading some of the lower-level people involved to plead guilty and cooperate against those higher up the ladder.

Even if prosecutors develop a compelling case, they might hesitate to proceed if prosecution would require revealing the secrets contained in some of the documents that Trump retained. This is sometimes referred to as “graymail” – the idea that a defendant can force prosecutors to drop a case involving classified information because putting the defendant on trial would require disclosing that information to the defense and the public. Depending on the nature of the classified information and the structure of any charges, the government may decide that a criminal prosecution should be declined in order to preserve the confidentiality of that information.

After the Mueller report, the attempted coup on January 6, 2021 and all of the other investigations surrounding Trump, indicting him for mishandling of classified information would feel a bit like prosecuting Al Capone for tax evasion. Even if prosecutors can develop a compelling case, deciding to indict a former president for the first time in our history would be a monumental step. In this and other investigations involving Trump, attorney general Merrick Garland will have to wrestle with all of the legal, social, and policy implications of bringing -- or not bringing -- such a case. I’m glad I don’t have to make that call.