Thoughts on Durham and the Sussmann Prosecution

After deliberating for only a few hours following a two-week trial, a federal jury this week acquitted D.C. attorney Michael Sussmann on a single charge of lying to the FBI. The quick not-guilty verdict was no surprise; the flimsiness of the government’s case was apparent from the start. This was a case that never should have been charged. The Sussmann prosecution is a cautionary tale of the damage a prosecutor can do when he loses sight of the line between criminal justice and politics.

The Sussmann Indictment

Sussmann is a prominent D.C. attorney who represented the Hillary Clinton campaign and the Democratic National Committee during the months leading up to the 2016 presidential election. In September 2016 he brought computer data to the FBI that suggested possible links between Donald Trump’s presidential campaign and Alfa Bank, a Russian bank with ties to the Kremlin.

The Alfa Bank allegations became a minor part of Crossfire Hurricane, the FBI’s broader investigation into potential ties between the Trump campaign and Russia. That investigation ultimately concluded that the data provided by Sussmann did not establish the suspected connection between the bank and the Trump campaign.

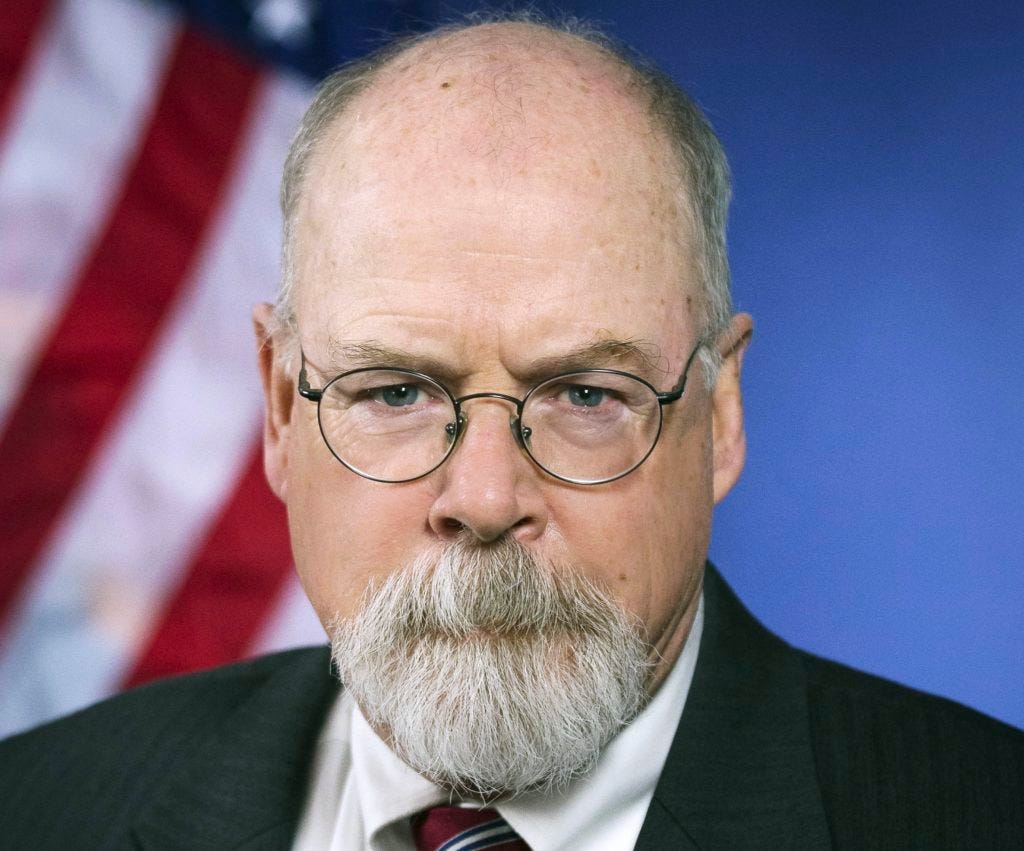

Former president Trump, of course, complained repeatedly (and still complains) that the FBI’s Russia investigation was a hoax, that the FBI and Clinton campaign conspired against him, and that the Obama administration “spied” on Trump and his campaign. Trump’s attorney general William Barr was also critical of the FBI’s Russia probe. In May of 2019, he assigned John Durham, the U.S. Attorney for Connecticut, to lead an investigation into any potential criminal wrongdoing in the Crossfire Hurricane investigation. In October 2020, Barr appointed Durham as a special counsel to continue that same investigation, thus granting Durham more independence and ensuring that his work could continue even after the Trump administration left office.

Last fall, just before the five-year statute of limitations expired, Durham charged Sussmann with making a single false statement during his meeting with the FBI in 2016 about the Alfa Bank data. The indictment alleged that during the meeting Sussmann said he was not acting on behalf of any client in bringing the data to the FBI. In fact, according to the indictment, he was acting on behalf of the Clinton campaign and a tech executive who collected the data.

The False Statements Charge

Sussmann was charged with one count of False Statements, 18 U.S.C. § 1001, a very common white-collar charge that broadly prohibits lying to the federal government. Unlike the related crime of perjury, it does not require that the statement was under oath. The statute is commonly used to charge lies on various government forms or applications. If you’ve filled out any kind of federal government paperwork, you’ve probably seen a notation at the bottom about how providing false information may be a criminal offense chargeable under 18 U.S.C. § 1001.

False statements is also frequently used to charge witnesses with lying to the FBI. A recent high-profile example was the prosecution of president Trump’s former national security advisor Michael Flynn, who was prosecuted for lying to the FBI about his contacts with the Russian ambassador in the weeks leading up to Trump’s inauguration. Trump confidant Roger Stone was also convicted of 1001 for lying to Congress about his work for the Trump campaign related to Wikileaks and the release of Democratic emails stolen by Russian hackers.

In any false statements prosecution the government must prove that the statement was actually false, that the defendant acted knowingly and willfully, and that the statement was material. Durham’s prosecution of Sussman stumbled over each of these requirements.

The Challenge of Proving Actual Falsity

The government’s star witness at trial was James Baker, the former FBI general counsel who met with Sussmann about the Alfa Bank data. The prosecution’s entire case hinged on Baker’s memory of a single alleged statement from their 30-minute conversation nearly six years ago. The meeting was not recorded, Baker took no notes, and there were no other witnesses.

Baker claimed on the stand that he was “100% confident” Sussmann told him during the meeting that he was not there on behalf of a client. But Baker had given conflicting accounts in the past about what exactly Sussmann said during their meeting, and the defense was able to hammer away at those inconsistencies. Sussmann’s defense also pointed out that Baker said he could “not recall” more than 100 times while on the witness stand. Yet when it came to this one particular detail of their conversation, his memory was supposedly rock-solid.

Recalling from memory precisely what was said in a brief conversation six years ago is virtually impossible. Given the nature of memory and human language, differences in recollection about precise wording and details are inevitable. And when a criminal charge is based on deliberate lying, minor variations in exactly what was said can make all the difference.

For example, one issue that arose during the trial was the distinction between representing a client and doing a particular act on behalf of that client. There was no doubt that Sussmann represented the Clinton campaign, and there was no doubt that Baker and the FBI knew that. But, as the defense pointed out at trial, just because you represent a client doesn’t mean that every action you take is on that client’s behalf.

There was evidence at the trial that the Clinton campaign did not ask Sussmann to bring the Alfa Bank information to the FBI. The campaign would have preferred that the data simply be given to the media, because it did not trust the FBI and thought the existence of an active investigation might actually make it more difficult to get the story out. So it could easily be true both that Sussmann represented the Clinton campaign and that he was not acting on the campaign’s behalf during this particular meeting. At the very least, those kinds of subtle distinctions almost inevitably raise a reasonable doubt about what precisely happened during a brief meeting six years ago.

It’s interesting to note that if the crime were common-law perjury (which requires testimony under oath) rather than false statements, an ancient doctrine called the “two witness rule” would bar such a prosecution. The two witness rule holds that a perjury prosecution cannot be based simply on a swearing contest, one person’s word against another’s. Prosecutors must have at least two witnesses to prove an alleged perjurious statement, or one witness plus some other independent evidence that supports the allegation of perjury. More modern perjury statutes have done away with the two-witness rule, and there is no such rule when it comes to 18 U.S.C. § 1001. But the wisdom of that rule still applies: resting a criminal prosecution on such “he said – he said” evidence is necessarily shaky, and only gets shakier with the passage of time.

These inherent uncertainties based on the nature of language and memory are why bringing a stand-alone prosecution based on a single unrecorded false statement witnessed by only one person is almost unheard of. It’s almost the definition of a reasonable doubt. That would be enough to stop most prosecutors -- but it didn't stop Durham.

The Requirement of Materiality

In addition to proving what Sussmann actually said (which, as we've seen, was difficult enough), the government had to prove any lie was material -- that it potentially mattered to the FBI. Here, too, the evidence in Sussman’s case fell far short.

The materiality requirement is usually not a significant hurdle for prosecutors. It means only that the statement had the potential to affect the actions of the government body to which the statement was directed. There’s no requirement that the government was actually influenced; in fact, a false statement can be material even if the government knows you are lying the instant that you utter it and never acts on it at all. All that matters is that the statement, by its nature, was the type that potentially could have made a difference.

Baker testified that if Sussmann had not allegedly made his false statement about not coming on behalf of any client, he would have treated the information with more suspicion or perhaps would not have agreed to meet at all. If believed, that testimony would be enough to establish materiality as a matter of law. But there were many reasons for the jury to doubt this evidence as well.

There was ample evidence – some of it contained in the indictment itself -- that the FBI knew full well who Sussmann was and what clients he represented. Given what Baker knew about Sussmann’s clients and connections, there was little reason to believe he would have acted any differently even if Sussmann did claim to be providing the computer data solely as a good citizen. After all, this meeting was taking place less than two months before a hotly-contested presidential election. The FBI wasn’t receiving the information in a vacuum and could not divorce the information from what it knew about its source. And the evidence at trial established that the Bureau would have investigated the allegations regardless of their origins. That at the very least raised a reasonable doubt about the alleged statement’s materiality.

The jury’s quick verdict suggests that it saw the allegations against Sussmann for what they were: a big “so what.” Jurors interviewed after the verdict said the case should not have been prosecuted and that they thought the government has better things to do. In class I sometimes refer to this as the, “no harm, no foul” rule – it’s not really a legal doctrine, but it does get the idea across. As a prosecutor, if at the end of your trial the jury is looking at you and thinking, “Why did you waste our time with this?” -- it doesn’t bode well for your case.

A Political Prosecution

From the start, the Sussmann prosecution felt more political than criminal. The lengthy indictment sought to paint a broad picture of a supposed conspiracy involving Clinton campaign operatives and the FBI. But most of the alleged activities involved legal opposition research and had nothing to do with the actual charge against Sussmann. Trying to dig up dirt on an opposing campaign and get the media to run with it may be unsavory. But it’s not illegal, and is a standard practice -- as the old saying goes, politics ain’t beanbag. Sussmann’s indictment seemed more designed to feed Trump’s fevered conspiracy theories than to lay out an actual criminal case.

Prosecutors at trial also sought to portray Sussmann’s supposed deception as part of a broader plot by the Clinton campaign to enlist the FBI in bringing down Trump. Prosecutors referred to Sussmann as a “privileged attorney” who tried to use his access to further his own political goals. In closing arguments, prosecutors argued that Sussmann and the Clinton campaign tried to engineer an “October surprise” involving the media and the FBI in order to damage Trump. To put it mildly, the jury didn’t buy it.

Some on the right will argue that, regardless of the outcome, Durham did a great service by bringing the case and “exposing” supposedly unsavory conduct by the FBI and the Clinton campaign. But criminal prosecution is about bringing specific, provable charges, not providing public reports on noncriminal conduct. The Department of Justice Inspector General already produced a lengthy report about the FBI’s handling of the allegations concerning the Trump campaign and Russia. That report concluded there were some legitimate problems with how certain aspects of the investigation were handled, but that the overall investigation was properly predicated and not politically motivated. It was not Durham’s job to create an alternate-universe version of those facts through the vehicle of a trumped-up criminal prosecution.

Of course, an acquittal does not necessarily mean that a prosecution was not righteous. But in this case, that's exactly what it means. A federal prosecutor is not supposed to indict unless he or she believes there is likely sufficient evidence to convince a jury of guilt beyond a reasonable doubt. It’s hard to see how any prosecutor could have looked at the facts of the Sussmann case and reached that conclusion in good faith.

Sussmann’s acquittal means the system ultimately worked, but that is cold comfort. Merely being indicted and put on trial is a tremendous ordeal – one that Sussmann never should have had to endure. Good prosecutors never forget the tremendous responsibility that comes with the powers they wield. In Durham’s zeal to provide fodder for Trump’s “deep state” conspiracy theories, he appears to have lost sight of this fundamental principle.

Durham’s probe has now lasted more than three years, and he has remarkably little to show for it. He obtained one guilty plea to a minor charge involving a former FBI attorney who admitted altering an email. He has another pending case against a Russian national, Igor Danchenko, for allegedly making false statements to the FBI about his involvement in the controversial Steele dossier. It’s unclear whether Durham’s investigation will lead to any more prosecutions. The Sussmann verdict will surely increase the pressure on the Justice Department to bring it all to a close.