The Sleeper Charge Related to January 6

How do you get Capone?

We learned this week that following the 2020 presidential election the Trump campaign hired an outside research firm to attempt to bolster its claims of election fraud. The firm, Berkeley Research Group, reportedly found nothing to suggest widespread fraud or that Trump won the election. The researchers also briefed Trump himself on those findings. Not surprisingly, the Trump campaign never made the findings public.

This new evidence that Trump knew his claims about the election were baseless could be key to proving what may emerge as the sleeper criminal charge related to January 6, 2021: fundraising fraud based on lies about the “stolen” election.

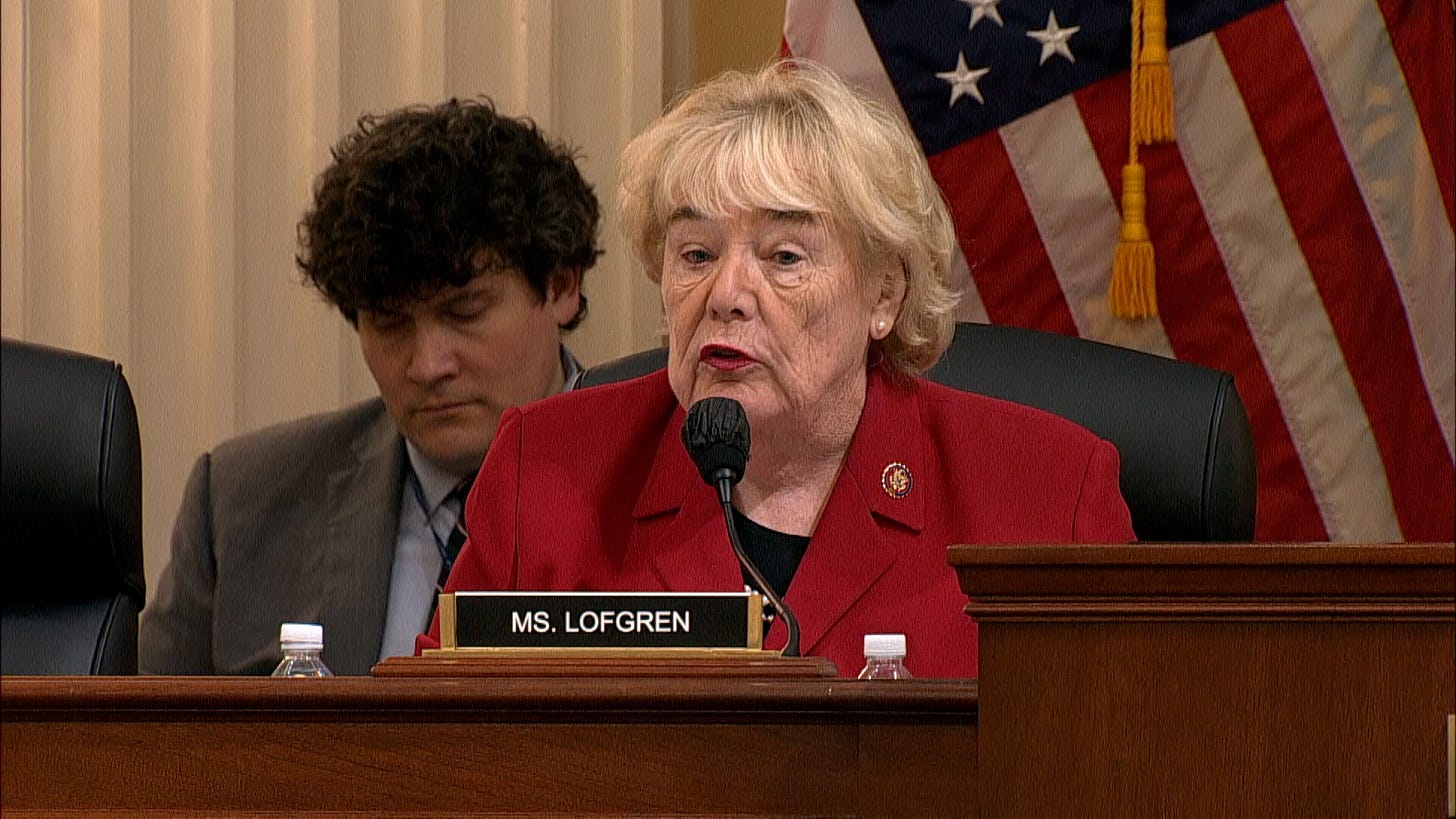

Rep. Zoe Lofgren presents the evidence of the “Big Rip-Off”

The Big Rip-Off

The House Select Committee on January 6 referred to this allegation as “The Big Rip-Off.” In Appendix 3 of its report, the Committee detailed how in the weeks following the election the Trump campaign, working with the Republican National Committee, raised more than $250 million – most of it from small donors -- through fundraising appeals that falsely claimed Trump had won. They claimed the election was “rigged,” that there had been widespread voter fraud, and that donations were needed to help stop the Democrats from “stealing” the election.

The fundraising emails urged donors to contribute to an “Official Election Defense Fund” – but no such fund actually existed. Most of the money raised did not go to vote recounts or fighting alleged election fraud. Instead, it went into a leadership political action committee, “Save America,” that Trump formed on November 9, 2020 – less than a week after the election. Directing the funds into a PAC rather than into the Trump campaign allowed Trump to spend the money with very few restrictions. But one thing Save America could not spend much money on was challenging the election – the Federal Election Campaign Act prohibited the PAC from spending more than $5,000 on recount and election-contest related expenses.

Let that sink in for a minute: Trump and his campaign raised millions by claiming they needed the money to fight the supposedly stolen election, and most of the funds they raised went to an entity that was legally prohibited from spending the money for that purpose.

The money raised to contest the election was actually used to build a huge political war chest for Trump. Most of it remains unspent. What has been spent has largely gone to conservative political groups, Trump-related entities, and entities run by or affiliated with his former staffers.

The House Report provides a few details. For example, a group of former staffers, including the speechwriter who wrote Trump’s speech on the ellipse on January 6, formed a company in January 2021 that Save America has since paid more than $300,000 for “consulting.” From January 2021 to June 2022 the PAC spent over $2.1 million on “legal consulting,” with about two-thirds of that money going to firms that represented witnesses called in the House January 6 investigation. It donated a million dollars to the Conservative Partnership Institute, a conservative nonprofit where Trump’s former Chief of Staff Mark Meadows is a senior partner. The Trump Hotel collection and Mar-a-Lago club received more than $300,000. Save America even paid $100,000 for “strategy consulting” to Herve Pierre Braillard, a fashion designer who works with Melania Trump.

Stop the steal, indeed.

Ode to Wire Fraud

Raising money by sending emails containing false claims and then using the money for other purposes is a textbook example of wire fraud -- and federal prosecutors love wire fraud.

In the spirit of Valentine’s Day, let me quote what federal judge (and former federal prosecutor) Jed Rakoff once wrote about mail fraud – wire fraud’s companion statute:

To federal prosecutors of white collar crime, the mail fraud statute is our Stradivarius, our Colt 45, our Louisville Slugger, our Cuisinart – our true love. We may flirt with RICO, show off with 10b-5, and call the conspiracy law “darling,” but we always come home to the virtues of [mail fraud], with its simplicity, adaptability, and comfortable familiarity. It understands us and, like many a foolish spouse, we like to think we understand it.

You may have a hard time getting this misty-eyed over a criminal statute. But mail and wire fraud are indeed the go-to charges for white collar prosecutors. (My daughter, who has heard me speak about my work over the years, says her takeaway is that white collar criminal law can be summed up as follows: “There’s a lot of bad stuff that happens that isn’t criminal. But if it is criminal, it’s probably wire fraud.” You know, that’s actually not bad.)

Wire fraud requires prosecutors to prove the defendant devised a scheme to defraud and in furtherance of that scheme sent an interstate communication, such as an email, text message, or phone call. “Wire” fraud is a bit of a misnomer because the statute also applies to radio transmissions, which includes all our modern wireless communications. A scheme to defraud is generally a scheme to deprive someone of money or property through knowing material deceptions or misrepresentations.

Using email to raise money by making knowingly false claims about a stolen election and then using the money for other purposes fits very comfortably within the wire fraud statute. The Berkeley Research Group news provides compelling new evidence – on top of all the failed lawsuits and the advice of his own attorney general and others -- that Trump himself knew he lost the election and the fundraising appeals were based on lies. Such evidence would be key to any fraud case.

Why Prosecutors Might Find Wire Fraud Appealing

There are good reasons wire fraud charges based on the “Big Rip-Off” might be especially appealing to special counsel Jack Smith, appointed to investigate Trump’s potential crimes in connection with January 6. Smith is also, of course, examining potential charges more directly related to the Capitol riot, such as seditious conspiracy (for which a number of Oath Keepers were recently convicted), inciting or aiding an insurrection, and obstruction of Congress.

Any prosecution of a former president for charges such as seditious conspiracy or inciting an insurrection will face unprecedented legal hurdles. Such charges will undoubtedly lead to claims of executive privilege, defenses based on the president’s first amendment rights, and other complex challenges. Even if not insurmountable, fighting over these issues could tie up the proceedings for months or years. We got another taste of this just this week, with former Vice President Pence announcing he will invoke a novel interpretation of the Constitution’s speech or debate clause to fight a grand jury subpoena from the special counsel seeking information about January 6.

By comparison, a charge of fundraising fraud could be relatively straightforward. It is unlikely to raise any of the complicated and novel questions that could bog down other charges. There is no remotely colorable argument that while engaged in political fundraising with the RNC Trump was executing the duties of his office. Any attempted claims of executive privilege or similar defenses could be easily and relatively quickly swatted aside.

As Judge Rakoff noted, another key benefit of wire fraud is its simplicity. The charge boils down to proof that the defendants hatched a scheme to rip somebody off and one of them sent an email. Lying and stealing are criminal law 101. It’s easy for prosecutors – and jurors – to wrap their heads around such a charge. Sedition and insurrection thankfully are unfamiliar territory and raise unfamiliar issues and challenges — but everyone understands a good con.

The most likely charge for Trump himself would be conspiracy to commit wire fraud. Presumably he did not send fundraising emails or collect money personally, but for a conspiracy charge that would not be required. The allegation would be that Trump agreed with his co-conspirators to engage in the fraud, while others handled the mechanics. And in the weeks following the election, Trump’s own Tweets to his millions of followers, making the same false claims about the stolen election and urging them to action, could be considered substantial acts in furtherance of that conspiracy.

Steve Bannon

“We Build the Wall”

Fundraising fraud charges are the kind of case prosecutors bring every day – and we don’t have to look far from the White House for an example. Former Trump advisor Steve Bannon was indicted by federal prosecutors in August of 2020 for a similar scheme. Prosecutors charged that Bannon and his co-defendants raised millions of dollars for “We Build the Wall,” a privately funded effort to erect a wall on the U.S.-Mexico border. Although promising that all funds would go toward wall construction, the defendants allegedly used most of the money to line their own pockets. The lead charge in that indictment? Conspiracy to commit wire fraud.

Trump pardoned Bannon in the federal case before leaving office. But New York prosecutors recently indicted him on similar state charges – which will be immune from a presidential pardon. Announcing the charges, Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg said, “It is a crime to turn a profit by lying to donors.” Yes, exactly — and in the federal system, the most likely criminal charge is wire fraud.

Prosecutors Follow the Money

There are signs that prosecutors are actively exploring the fundraising fraud allegations. There have been multiple reports of grand jury subpoenas seeking documents and testimony about Trump’s post-election fundraising and the finances of Save America and other Trump-affiliated organizations — even before the special counsel was appointed. This suggests prosecutors are working to follow the money and see where the funds raised to “stop the steal” were actually spent – essential evidence for a potential fraud charge.

Al Capone

How You Get Capone

Fundraising fraud does not go directly to the heart of the efforts to overturn the election. There’s a reason the House Committee summarized these allegations in an Appendix, not in the main body of its report.

Prosecuting Trump for fleecing his donors may seem a bit like prosecuting Al Capone for tax evasion: the charge doesn’t represent the true nature of the harm the defendant caused. That may not feel very satisfying. But as the tax charges did with Capone, it could offer prosecutors a relatively clean shot at one aspect of Trump’s alleged wrongdoing when other charges are far more difficult to prove.

This doesn’t mean prosecutors won’t or shouldn’t also bring charges such as seditious conspiracy or obstruction. The evidence for those charges also appears compelling, and those who sought to overturn the election need to be held accountable. But it’s easy to see why prosecutors might consider charges of fundraising fraud to be relatively low-hanging fruit.

Whether alone, or in combination with other charges more directly related to the assault on the Capitol, don’t be surprised to see prosecutors reach for their Louisville Slugger to take a swing at the Big Rip-Off.

One of your best, Randall!

This is really interesting, Randall. Thanks.