The Status of the Michael Flynn Case

Update: On June 24, 2020, in a 2-1 decision, the D.C. Circuit granted the petition for mandamus and ordered Judge Sullivan to dismiss the case. Sullivan or one of the circuit judges may request en banc review by the full court.

Further update: On August 31, 2020, the en banc D.C. Circuit reversed the panel opinion on mandamus by an 8-2 vote, sending the case back to Judge Sullivan to rule on the motion to dismiss.

The Michael Flynn case is no longer just about a senior government official who lied to the FBI. The prosecution of president Trump's former national security advisor has become a symbolic struggle over the separation of powers and a showcase for allegations of corruption within the Trump Justice Department. Regardless of the outcome of these court proceedings, Flynn is unlikely ever to see the inside of a jail cell. But how the case plays out over the next few weeks will be an important test of the ability – and willingness – of the judiciary to push back against the Trump administration’s abuse of the justice system.

Procedural History of the Flynn Case

Flynn pleaded guilty in December 2017 to one count of lying to the FBI. During his guilty plea, Flynn admitted under oath that he had lied to FBI agents about his contacts with the Russian ambassador in December 2016 on behalf of the incoming Trump administration. He confirmed his guilt under oath a second time after his case was transferred to judge Emmet Sullivan. Flynn’s sentencing was substantially delayed while he cooperated with the government during the Mueller investigation.

Once the Mueller probe was concluded, however, Flynn changed his tune. Last summer he fired his respected defense team from the leading D.C. firm of Covington & Burling and hired Sydney Powell, a vocal DOJ critic and Fox News regular. In recent months Powell moved to withdraw Flynn’s guilty plea and to have the charges dismissed, claiming Flynn was an innocent victim of government misconduct. Those motions are still pending before Judge Sullivan.

But the real bombshell in the case landed last month. On May 7 the Justice Department filed a motion to dismiss Flynn’s case. After defending Flynn’s prosecution in court for more than two years, DOJ told the court it now believed Flynn had not actually committed a crime and never should have been prosecuted in the first place.

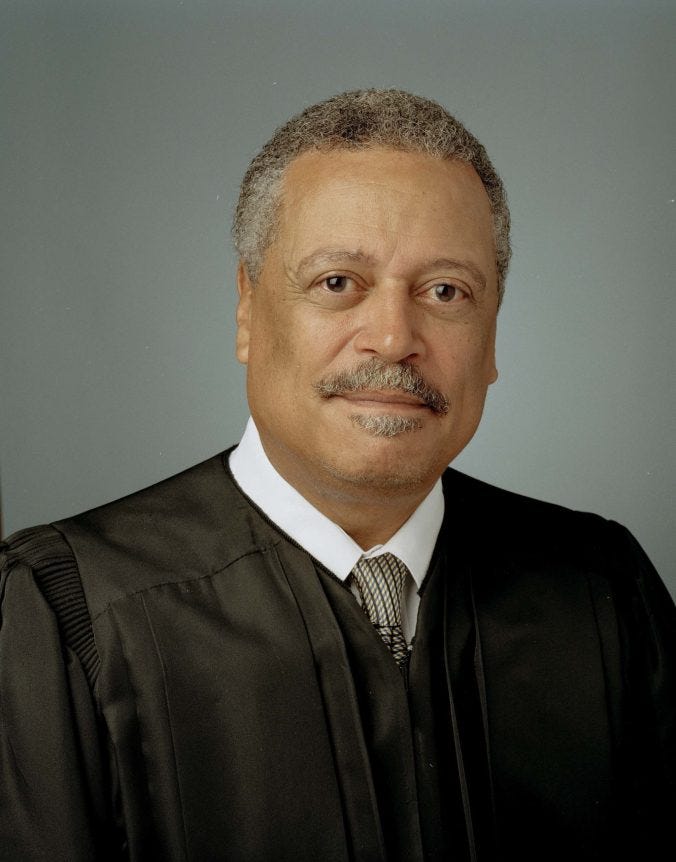

In response to this startling motion, Judge Sullivan made it clear he wasn’t simply going to accept the government’s claims at face value. Since Flynn and the DOJ were now on the same side, Sullivan appointed a respected former federal judge, John Gleeson, to present any legal arguments against the government’s motion. He also asked Gleeson to advise him on whether Flynn should be charged with contempt for lying during his plea proceedings.

Rather than wait for Judge Sullivan to rule, on May 19 Flynn’s attorney took the unusual step of asking the U.S. Court of Appeals for the D.C. Circuit to issue a writ of mandamus – an order telling Sullivan that he has to grant the motion to dismiss without any further proceedings or delay. The court of appeals asked to hear arguments on the mandamus petition, and Sullivan appointed prominent D.C. attorney Beth Wilkinson to represent him. The Justice Department filed a brief in support of Flynn, and the court of appeals heard arguments on the mandamus petition on Friday, June 12.

As of today, the posture of the case is that Sullivan has a hearing set for July 16 on the motion to dismiss. But before that happens, we expect to hear from the D.C. Circuit on whether it will grant Flynn’s petition for mandamus. If it does, it will order Sullivan to grant the motion and the case will be over. If the circuit court denies the petition, Sullivan will hold the hearing and then either grant the motion to dismiss or deny it and set Flynn’s case for sentencing.

There are two different types of issues presented by these various legal maneuvers: the merits and the process. The merits issue is whether the government’s motion to dismiss should be granted and how much discretion, if any, Judge Sullivan has to review the government’s purported reasons for the dismissal. The process issue is who gets to decide those questions in the first instance: Judge Sullivan, or the Court of Appeals?

Who Gets to Decide?

The process issue is far easier. There are definitely novel and difficult questions raised by the government’s motion to dismiss. But in the ordinary course of legal proceedings, it’s the trial judge who gets to decide those issues first. Sullivan may well end up granting the motion to dismiss, and the case will be over. If he denies the motion, Flynn could appeal to the D.C. Circuit at that time. But there is no justification for the extraordinary remedy of a writ of mandamus, which would allow Flynn (and the government) improperly to sidestep the proceedings before Sullivan.

Flynn and the DOJ argue that mandamus is appropriate because Judge Sullivan has no discretion here. There is no longer an active dispute before the court, because both the defense and the prosecution agree they want the case dismissed. Because the executive branch has sole discretion to decide whether to prosecute, they argue, the judge lacks the constitutional authority to keep the case alive.

One difficulty with this argument is that Federal Rule of Criminal Procedure 48(a), which governs motions to dismiss, says the government may dismiss a case only “with leave of court.” As Judge Wilkins repeatedly pointed out during the D.C. Circuit argument on Friday, that language must mean something. It suggests there is a role for the court to play and that the judge is not merely a rubber stamp. Attorneys for Powell and the DOJ have struggled to explain how “with leave of court” actually means that the court has no choice.

Whether a judge has the authority to deny a motion to dismiss that is agreed to by both sides is an unsettled question. In Rinaldi v. United States the Supreme Court stated:

The words "leave of court" were inserted in Rule 48(a) without explanation. While they obviously vest some discretion in the court, the circumstances in which that discretion may properly be exercised have not been delineated by this Court. The principal object of the "leave of court" requirement is apparently to protect a defendant against prosecutorial harassment, e.g., charging, dismissing, and recharging, when the Government moves to dismiss an indictment over the defendant's objection. But the Rule has also been held [by lower courts] to permit the court to deny a Government dismissal motion to which the defendant has consented if the motion is prompted by considerations clearly contrary to the public interest. (emphasis added, citations omitted)

That’s the issue presented in Flynn’s case: whether Judge Sullivan has the authority to deny the motion to dismiss based on a finding that the motion was prompted by “considerations clearly contrary to the public interest” – namely corruption within the DOJ and the fact that Flynn is a political ally of president Trump’s. The Supreme Court did not decide in Rinaldi whether a judge has that kind of authority, and that question remains unresolved.

The Need for "Regular Order"

The fact that Sullivan's authority is unsettled is why the mandamus petition should be denied. Mandamus is an extraordinary and unusual remedy. It requires the law to be so clear that there is no possible debate about the proper outcome; the movant must be “clearly and indisputably” entitled to relief and have no other adequate remedy. That’s simply not true in this case. The legal standards governing this motion are unresolved, not “clear and indisputable,” and Flynn has an adequate remedy: let the judge decide his motion, as in any other case.

As Judge Henderson repeatedly pointed out during the D.C. Circuit argument, "regular order" demands that the trial judge, Judge Sullivan, gets to decide those difficult issues in the first instance. That will allow the facts to be fully developed and the arguments on both sides to be heard, and will allow Sullivan to make findings of fact and rulings of law. An appeal to the D.C. Circuit could then follow, if necessary. That’s how our court system works. You don’t get an exception for being the president’s pal.

The mandamus petition argues that Sullivan has no authority to deny the motion to dismiss. Sullivan may well end up agreeing. But Flynn is saying Sullivan can’t even consider the question; can’t even hear the arguments on both sides and make a decision. That’s wrong.

I think the D.C. Circuit is likely to deny the mandamus petition. Judge Sullivan should get to decide the motion to dismiss before the court of appeals gets involved.

The Merits of the Motion to Dismiss

On the merits, the government’s motion to dismiss is remarkably weak. Judge Gleeson, the amicus appointed by Judge Sullivan, concluded that the arguments advanced by the government are “pretextual” and that the motion is “riddled with inexplicable and elementary errors of law and fact.” I think Gleeson is correct. The legal arguments are frankly laughable. They are also inconsistent with arguments the government itself has made repeatedly over the more than two years this case has been pending.

The government argues first that it now does not believe Flynn’s lies to the FBI were material, as required by the false statements statute. But materiality is a very low bar -- a statement need only have the potential to influence some government decision. Flynn’s lies to the FBI about his Russian contacts, made in connection with the FBI’s investigation of Russia and the Trump campaign, easily meet that standard. As Judge Gleeson put it:

In short, pursuant to an active investigation into whether President Trump’s campaign officials coordinated activities with the Government of Russia, one of those officials lied to the FBI about coordinating activities with the Government of Russia. It is hard to conceive of a more material false statement than this one.

The government claims the lies could not be material because they were not related to a properly predicated investigation of Flynn. This too is nonsense. You don’t have to be the subject of an active investigation yourself to lie to the FBI, or for the FBI to have a reason to interview you. Whether a particular investigation was properly opened or was about to be closed are, as Judge Gleeson noted, simply matters of "bureaucratic happenstance that had no bearing on whether the FBI could or should interview Flynn" about his Russian contacts. In other words, even if the FBI screws up some internal paperwork or procedure before your interview, you don’t get a free pass to lie.

The government also claims it now believes it could not prove that Flynn intentionally lied. Of course, it doesn’t have to prove that, because Flynn himself has already admitted it repeatedly, under oath. He also lied to others in the Trump administration, which is why he was fired after only a couple of weeks on the job. In his brief, Judge Gleeson describes in meticulous detail the various false statements Flynn made during his interview and why they were false.

Judge Sullivan has already ruled – agreeing with earlier arguments made by the prosecutors – that Flynn’s statements were material. Flynn himself has repeatedly acknowledged under oath that he lied to the agents. But the government now claims it could not prove materiality or that Flynn lied. It’s easy to see why Gleeson concluded that the government’s arguments are legally unsound and are a transparent effort to drop the case simply to benefit an ally of president Trump.

What Should Sullivan Do?

The legal arguments in support of the government’s motion to dismiss may be laughable, but that doesn’t necessarily mean that Sullivan should, or can, deny the motion. As noted above, the “leave of court” requirement in Rule 48(a) indicates the court does not have to simply serve as a rubber stamp in the face of such obviously pretextual arguments for dismissal. And the Supreme Court’s footnote in Rinaldi at least notes the possibility that the motion could be denied if contrary to the public interest. But when both the prosecutor and defense agree a case should be dismissed, can the judge really insist that the case go forward? And what would that look like?

In his brief filed on June 10, Judge Gleeson argued that Sullivan should deny the motion and proceed to sentence Flynn. Gleeson pulled no punches, accusing the DOJ of a “gross abuse of prosecutorial power.” He argued that the motion to dismiss was an "unconvincing effort to disguise as legitimate a decision to dismiss that is based solely on the fact that Flynn is a political ally of President Trump."

As Gleeson points out, the integrity of the judicial branch is at stake here too. The judge is not required to be complicit if he finds an abuse of the prosecutor’s authority:

The Executive Branch had the unreviewable discretion to never charge Flynn with acrime because he is a friend and political ally of President Trump. President Trump today has the unreviewable authority to issue a pardon, thus ensuring that Flynn is no longer prosecuted and never punished for his crimes because he is a friend and political ally. But the instant the Executive Branch filed a criminal charge against Flynn, it forfeited the right to implicate this Court in the dismissal of that charge simply because Flynn is a friend and political ally of the President. Avoiding precisely that unseemly outcome is why Rule 48(a) requires “leave of court.”

Gleeson argues that accepting the government’s false reasons for dismissal would undermine the public’s confidence in the rule of law by demonstrating that the Trump DOJ may act to benefit the president’s political cronies with impunity.

Admittedly, denying a motion to dismiss supported by both sides could present difficulties in some cases. As Flynn and the government’s lawyers argued in the D.C. Circuit, a judge has no mechanism to compel prosecutors to move forward with a case they want to dismiss. But in the current posture of Flynn’s case, that’s not really an issue. Flynn’s prosecution is essentially over; there is nothing more that prosecutors need to do. All that remains is sentencing, and prosecutors have already filed memoranda setting forth their positions on that. Sullivan could easily proceed to sentence Flynn even if the current prosecutors decline to speak at the hearing.

I don’t know how Judge Sullivan will ultimately decide the motion to dismiss. I wouldn’t be surprised if he grants it in the end. But if he does, it won’t be because the government is right on the merits. It will be because he agrees that in our constitutional structure the executive branch has absolute authority over decisions to prosecute. He may rule that even if a prosecution is dropped for corrupt reasons, the remedy has to lie elsewhere. The remedy is not to try to force the prosecution to proceed -- which, in most cases if not this one, would be impossible anyway. But if Sullivan decides a judge does indeed have the authority to deny a motion to dismiss because it is contrary to the public interest, he will likely deny the motion. The posture and facts of this case make it a great candidate for such a denial.

Won’t Trump Just Pardon Flynn Anyway?

Many feel that this entire proceeding is an exercise in futility. After all, even if Sullivan ended up denying the motion to dismiss, sentenced Flynn to prison, and that was upheld on appeal, it seems almost certain that president Trump would step in and pardon him. So as I mentioned at the outset, no matter how this all turns out, Flynn is unlikely ever to see the inside of a jail cell.

But regardless, this is a case where the process is important. It’s important first to uphold the principle that the president’s buddies, just like everyone else, have to pursue “regular order” in the court system. They don’t get to go over the head of a judge whose rulings they might not like and get the court of appeals to order the judge to rule their way. They need to play by the rules, present their arguments to the judge, and then appeal if necessary, just like everyone else.

Denial of the motion followed by a pardon would actually be a better result because, oddly enough, it’s more honest. If Trump wants to exercise his pardon power to benefit his political allies, he should have to take whatever political heat goes along with that. The motion to dismiss was Attorney General Barr’s attempt to do Trump’s dirty work for him – to get Flynn off the hook by pretending that justice demanded it. That should not be allowed. If Trump wants to use his power corruptly to benefit his political crony, he should have to own it.

Finally, even if Sullivan ultimately grants the motion, holding a hearing where the government has to defend the motion will provide a public airing of the government’s actions and purported reasons for the dismissal. Those who argue Sullivan must grant the motion say that even if there is corruption underlying the motion, the remedy is for the public to hold that against the politically-accountable executive branch. But that accountability can’t happen if the true reasons for the dismissal remain concealed.

During the D.C. Circuit argument, the government's attorney objected to the idea of a hearing where the government may "have to explain itself." That objection is telling. The "leave of court" requirement must mean, at the very least, that Judge Sullivan is entitled to an explanation. He's entitled to explore why the government has reversed course after pursuing a case before him for more than two years. By accepting briefs, holding a hearing, and issuing a ruling containing findings of fact, Judge Sullivan can shine some sunlight on DOJ’s misconduct, even if he ultimately grants the motion. That will provide voters with information they can use to evaluate the conduct of Trump's DOJ when they go to the polls in November.

In the end, that might be the most helpful outcome of all.

Like this post? Click here to join the Sidebars mailing list